Capital Dream

The Seduction of Champagne, Chauffeurs and the Cult of the 1980s Yuppie

The images one encounters upon entering a prestige mall in East Asia, or in my case, Bangkok; are scenes of people living their lives through shopping bags stamped with the most recognizable logos. From the democratic appeal of H&M to the continental refinement of Dior and Chanel (even if what’s inside is only a lipstick), these visuals form a compelling narrative of consumerism deeply woven into the modern fabric of society, particularly in the East. The mall itself, grand in scale and architecturally sophisticated, stands as a contemporary temple of desire. Inside, boutiques from the world’s most esteemed houses line the polished halls, each attended by poised sales associates posing as personal shoppers, curating the illusion of privilege.

This is not mere commerce but a performance of status and belonging. Everyone wants to feel important, to be seen, recognized, and valued. What greater expression of that desire than walking into Hermès, being ushered into a private salon by an elegant concierge, speaking the language of refinement, and leaving with a new Kelly bag in hand—knowing that money alone cannot buy the experience, only access. What fascinates me is that this cultural tableau, this Asian aspiration for status and luxury, is hardly new. Before the East fully gravitated toward this life, the West had already set the stage. And nowhere was that performance more seductive than in the United States during the 1980s.

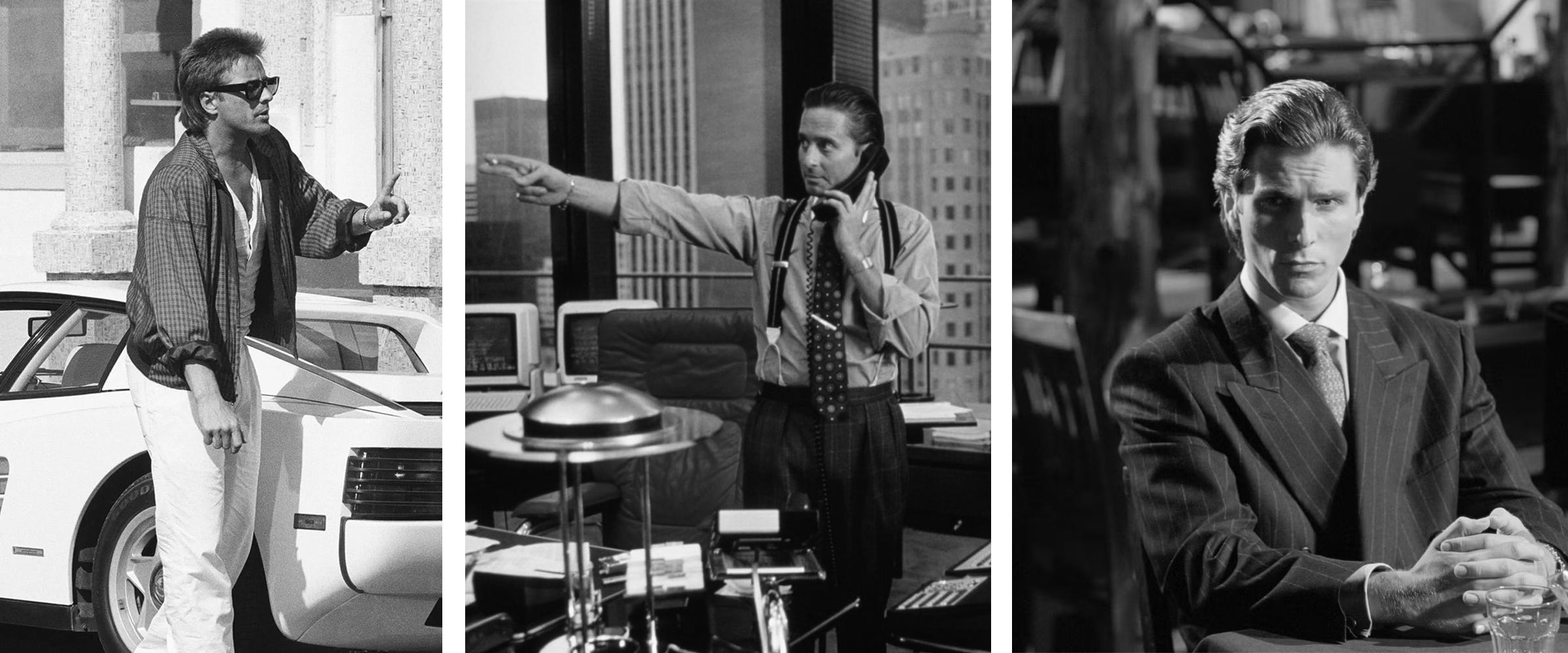

White Testarossas, Cerruti 1881 pinstripe suits, Motorola phones on glass-topped desks high above Manhattan…these were the aesthetic signatures of the American 1980s. It was a decade of glittering ambition and unapologetic materialism, where confidence was lacquered in pomade and ambition smelled faintly of leather upholstery. The visual excess of that era was rooted in its economic ideology. Reaganomics, the pro-business philosophy of the time, slashed taxes and regulations with the promise that wealth would ‘trickle down’ through society. Mergers and acquisitions became the engines of economic expansion, transforming the stagnant spirit of the 1970s into a decade of restless opportunity. The result was newfound wealth among the middle and upper classes and an explosion in consumer confidence. Luxury industries flourished: real estate boomed in the Hamptons, Valentino and Armani redefined power dressing, the Porsche 911 and Lamborghini Countach became emblems of achievement, and fine dining turned into an expression of identity. By the mid-’80s, success wasn’t merely about earning—it was about displaying. Money had become the medium through which one spoke to the world.

Then came the Yuppie, the living archetype of the age. Young, ambitious, and intoxicated by the power of capital, the Yuppie embodied success as both a pursuit and a performance. It’s remarkable how swiftly society shifted from the hippie’s free spirit of the 1970s—those who once rejected capitalism and hierarchy in search of spiritual liberation—to a new generation wrapped in Cartier watches, Ralph Lauren suits, and the metallic scent of aspiration. Within a single decade, the pendulum swung from collectivism to individualism, from “make love, not war” to “make money, not excuses.”

If the 1970s dreamed of changing the world, the 1980s replied, “If you can’t change it, own a BMW and a Manhattan condo.”

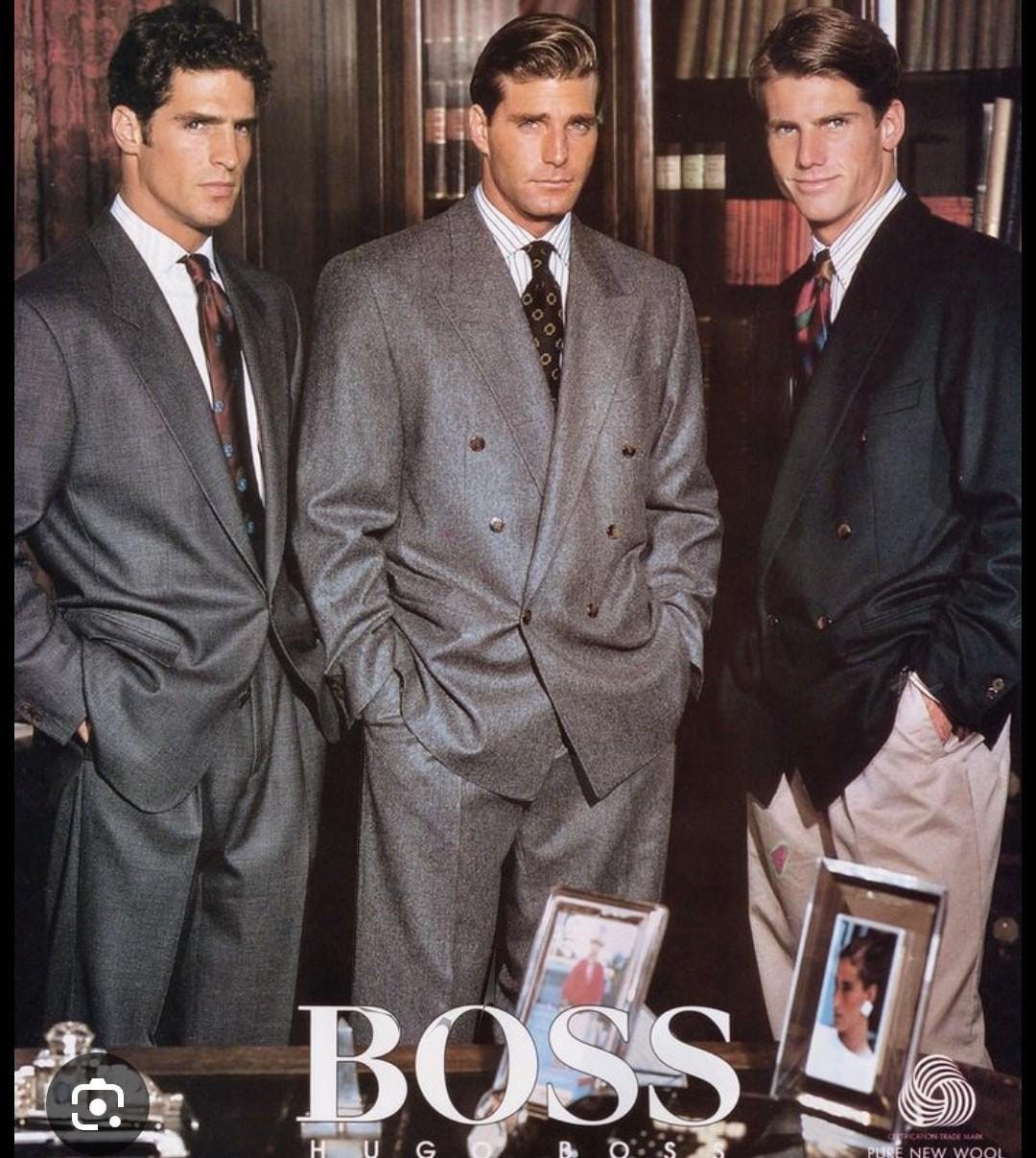

The Yuppie lived by a new trinity: Ambition, Careerism, Materialism. Style became its visual language—broad-shouldered tailoring, bold yet polished patterns, high-quality garments worn with intent. Gold replaced silver, paisley overtook plain, and the discreet charm of mid-century dress gave way to an unapologetic aesthetic of power. Women, too, joined the movement in shimmering blouses and pencil skirts that spoke of confidence rather than submission. Advertisements and magazines of the time mirrored this transformation, turning glossy pages into portraits of success that turned aspiration into a cultural habit.

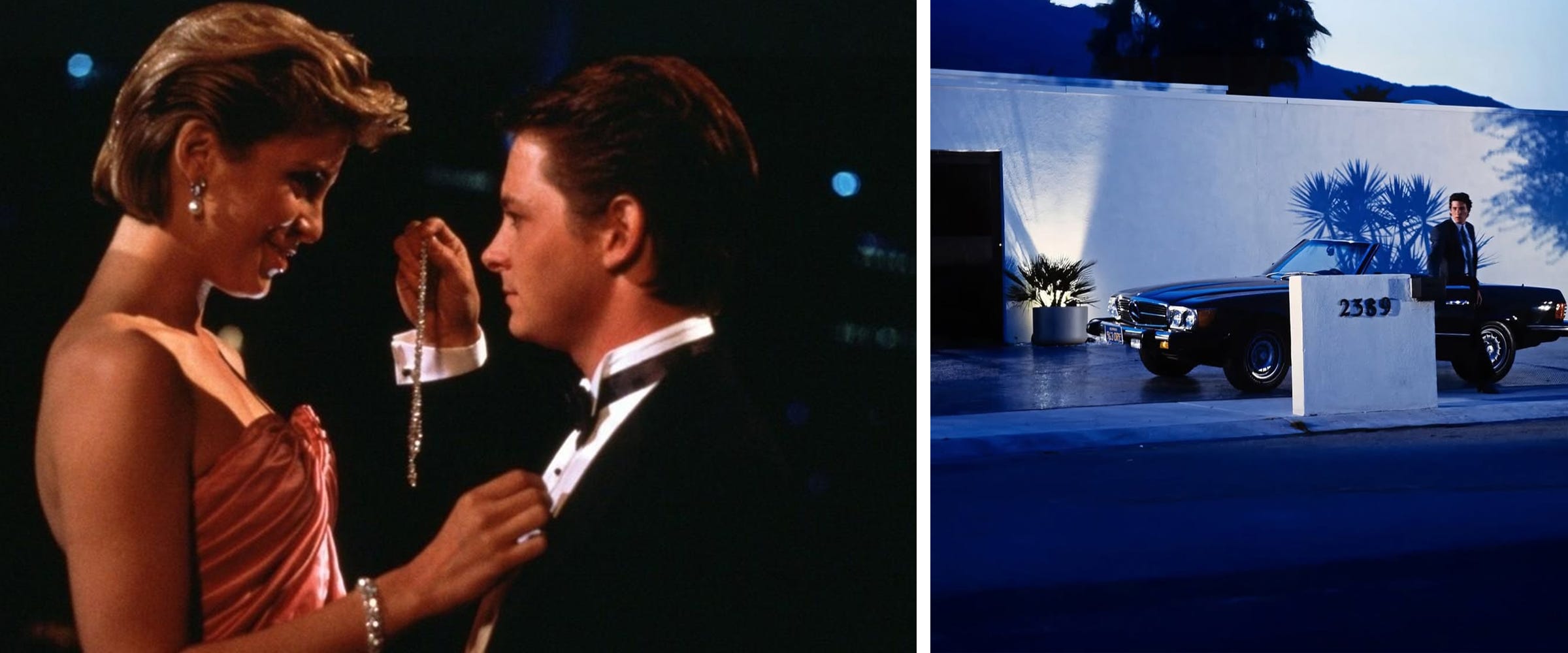

Few lines capture the essence of the 1980s more perfectly than Gordon Gekko’s declaration in Wall Street: “Greed is good.” Clad in a double-breasted Cerruti suit, Gekko became both villain and hero—a mirror reflecting the moral paradox of his time. He was ruthless, amoral, and entirely captivating. What fascinates me most is how a fictional character transcended the screen to become a living role model for thousands of young professionals, some of whom still echo his philosophy today. But perhaps that’s the point. When the world around you equates worth with success, the boundary between virtue and vanity blurs easily. It’s hard to resist the intoxicating pleasure of achievement when it’s served in a stretch limousine with Dom Pérignon in hand. To sit there, looking out at the city lights, thinking, “I have arrived,” is to understand the quiet seduction of status itself. The 1980s didn’t just sell products; it sold a dream (and it sold it well.)

The 1980s were a decade of contradictions, where optimism and ostentation danced in perfect sync. The Yuppie became both the symbol of opportunity and the face of excess, embodying the fine line between ambition and greed. Shopping malls rose as the new cathedrals of consumerism, their marble corridors echoing with the hum of credit card transactions and perfume spritzes. Luxury goods became the vocabulary of identity; a stretch limousine, a champagne flute, or a Rolex wasn’t just an accessory but a declaration of being. Consumer culture, driven by economic boom and media glamour, infiltrated every corner of life—sometimes inspiring, often gaudy, but always distinctively 1980s. It was an age of high glamour and low spirit, where human desire dressed itself in aspiration and consumption became the closest thing to faith.

Looking around today, in the metropolises of the 2020s, the reflection is eerily familiar. The Ralph Lauren polos remain. The Porsche 911 still commands reverence (though its badge reads 992 instead of 930.) The logos of Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Chanel continue to dictate social hierarchies. And once again, people find reassurance in the illusion of status. The stage may have changed, but the performance continues. The world, it seems, is still learning that greed, in all its golden shimmer, is not always good.

Fabulous 🤩👏✨you nailed it my friend 😉👏 spot on. I am aware of this era and times in the 80's being born 1981 and knowing all about the scenes 😉🩷✅💯 born and raised around most areas but I know a fair more about it than my peers. And I'm proud to have be involved with the choices I was given xoxo 😘😘😘👏😁✨🩷💜❤️ Absolutely Gold my friend 😁👏❤️💜🩷 well done ✅🩷😊