Cities Without Souls

How modernity, alienation, and art reveals about life in the metropolis

“Modernity is the transient, the fleeting, the contingent; it is one half of art, the other being the eternal and the immutable.” — Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life (1863)

Modernism is a cultural and artistic movement that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, characterized by a deliberate break with tradition and a search for new forms of expression in response to modernity.

Due to the occurrence of disruptive emergence during the 19th-century landscape — from industrialization and urbanism to shifted social norms — the way of human life has been reshaped by speed, convenience, and fleeting experience. The nature of modernity seems to intensify day by day.

Technology, science, rationalization — the great intellectual creations that humanity articulated into forms allowing civilization to achieve more in a single century than in the previous millennium — have also shaped life in modern time into a very specific form. An isolation of the soul, in the big metropolis, living and existing for the capitalist machine: either in monetary pursuit or the endless ladder of status and clout.

Thus, the form of the metropolis has occurred since then. With the economic “center” gathered within a single capital, people from all across the country found their way into the city. Some made their fortune as entrepreneurs, some achieved a decent life as thinkers or the knowledge class, but most ended up with a stripped soul in the factory 9–5.

When masses needed to live within it, the inevitable came: the fact of limited space. This forced the cityscape into density — tall buildings, crowded streets, and more; things that I believe you readers have observed and are already aware of.

While there are some capitals that successfully blended heritage and utility altogether — those names do not include Bangkok. I can tell, from the experience of living in this city for two decades… it is a chaotic, contradictory place to be in.

From an external point of view, Bangkok is a tropical paradise. With one of the most convenient infrastructures, iconic culinary culture, plenty of tourist attractions, and even an urban modern nightlife with endless possibilities to offer — the only rule is that you must have enough capital to experience them. People from strong-currency countries usually pass that criteria automatically.

However, beside the glamour of modern offerings, the heritage of temples and grand palaces — within the same acres, the same blocks — lie poverty, alienation, and soulless lives, either drained by the instability of modern time or by a cityscape that was never designed for living in, only living on.

My view on modernity and the metropolis is this:

I agree that it is inevitable, due to the evolutionary aspect of human nature — but it needs to find a middle ground. An experience that contains soul, life, aesthetic, beauty, love, romance, and passion within it.

Yet it is a very, very tough thing to achieve. From the early occurrence of the term being coined to the new millennium, humanity seems to struggle endlessly with the cost of evolution in the name of modernism.

Perhaps we need to look back — just a few centuries ago — and you’ll notice that modernism has been a topic of contradiction ever since. From New York to Tokyo, through various eyes and perspectives, artists and thinkers questioned the existence of the metropolis and the new world paradigm in their own alluring ways.

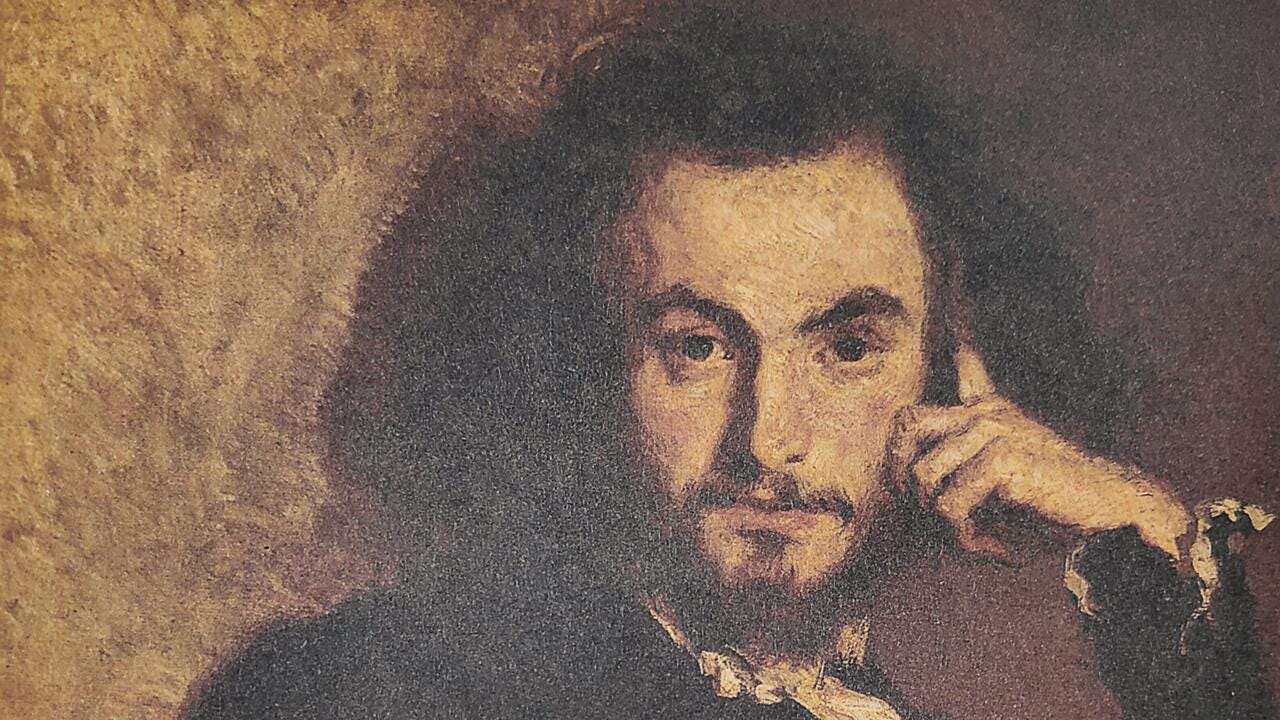

Charles Baudelaire — Le Flâneur

Ladies and gentlemen, I want you to imagine 19th-century Paris — the birth of the Paris you see and somewhat romanticize through Instagram these days. With the occurrence of Haussmann’s renovation, Paris transformed: from dense, crowded streets lacking space and aesthetic, into the symbol of the modern city of its era.

However, there was one eye that saw this not as evolution, but as decadence of the soul — Charles Baudelaire.

He was arguably the first true modern soul; part poet, part existential dandy — a man who didn’t just witness the birth of modernity, but seduced it, cursed it, and ultimately died from its poison. His invention wasn’t merely a poem, but a persona: Le Flâneur — the idle urban stroller who watches the city with detached curiosity.

A man neither fully inside the city nor completely outside it, but a flâneur who floats through the spectacle of urban life… absorbing its patterns, its absurdities, its lies. In Baudelaire’s hands, wandering became philosophical. The act of observing the crowd — without being absorbed by it — became a form of resistance. Detached, ironic, hyper-aware — and deeply alone.

Paris, through his eyes, wasn’t romantic because it was beautiful. It was romantic because it was decaying with style. He saw elegance as a mask for rot, perfume as a disguise for death, beauty as something artificial — and that’s precisely what made it divine. No wonder his works are filled with prostitutes, dying flowers, and alleyways dripping with symbolism.

What Baudelaire offered was not a celebration of the modern world, but a poetic lens through which to survive it. He taught us that beauty doesn’t lie in clean lines or eternal truths — but in fleeting moments, stolen glances, decaying flowers in silver vases, and cigarette smoke swirling under gaslight.

He made alienation aesthetic.

He made observation sacred.

And in doing so, he built the philosophical foundation not only for modernism, but for modern consciousness itself.

Modernism, for Baudelaire, is the poetry of collapse — romanticized, stylized, and framed by a man who walked the city with a broken heart and a sharp pen.

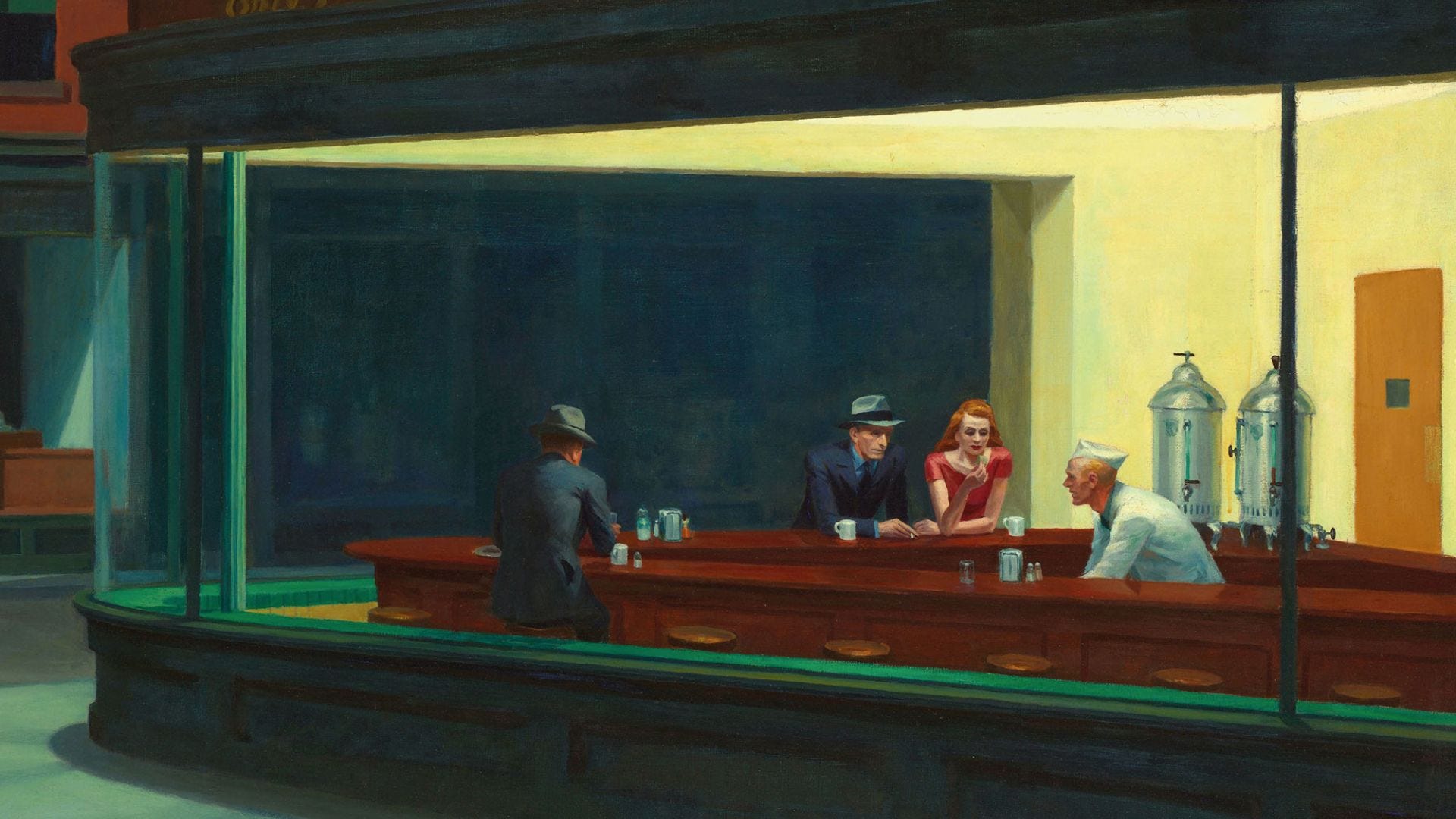

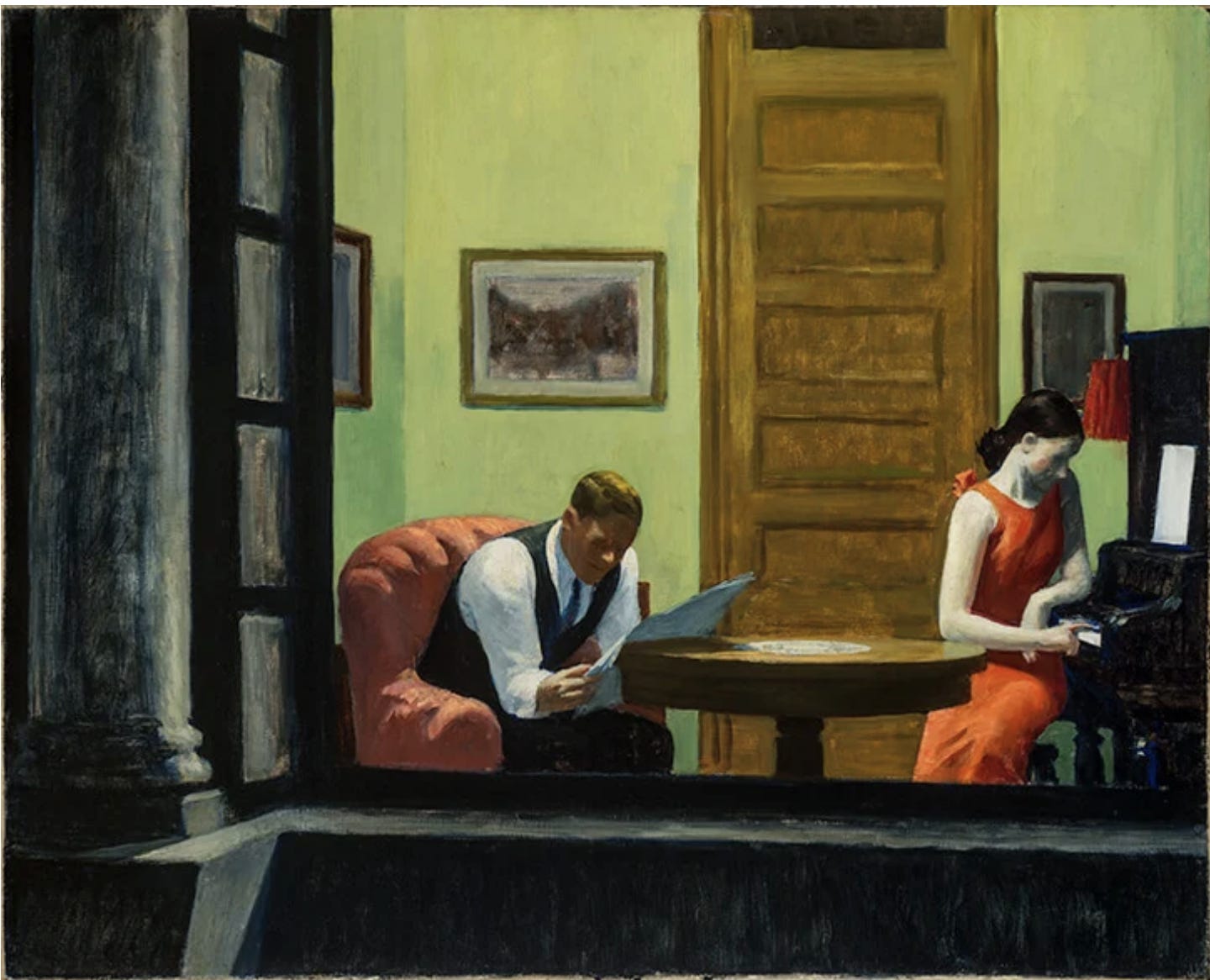

Edward Hopper — The Lonesome Painter

The United States in the early to mid-20th century was something special — a nation that reigned supreme. A booming economy, suburban expansion, neon signs, and the rise of consumer culture; all of this happening while global warfare loomed in the background. Still, the idea of the American Dream seemed alive, advancing through the cityscape of the era.

But beneath that glossy exterior, something darker crawled: a loss of spirit. Cities grew taller, homes grew wider — but human hearts grew quieter. The landscape became efficient, sanitized, and profoundly lonely.

And there was one man who saw it all — Edward Hopper.

Yet he didn’t scream about it.

He painted it.

Slowly. Methodically.

His canvases weren’t crowded with action or political symbols, but stripped bare and filled with stillness. A lone man at a gas station at dusk. A woman sitting by a window in a hotel room. A couple in a diner, sitting close — yet emotionally miles apart.

Hopper’s style is deceptively simple: sharp lines, stark lighting, minimal expression. But within that economy, he achieves a kind of emotional brutalism. His colors are cold, his light unnatural, his settings eerily static. It’s cinematic — but in slow motion, as if time itself is holding its breath.

The stillness doesn’t soothe; it stings.

And always, the figures — even when together — are utterly alone. Hopper gives us public solitude. People surrounded by civilization, yet untouched by it. This isn’t loneliness caused by geography — it’s existential. You’re in the city, yet you’re adrift.

He stripped away the patriotic myth and suburban fantasy, revealing a country built on quiet desperation. No propaganda. No heroism. Just a man, a light, a window — and the haunting question of who we are when no one’s watching.

Modernism, for Hopper, is the architecture of isolation — rendered in clean lines, artificial light, and the unbearable silence of ordinary moments.

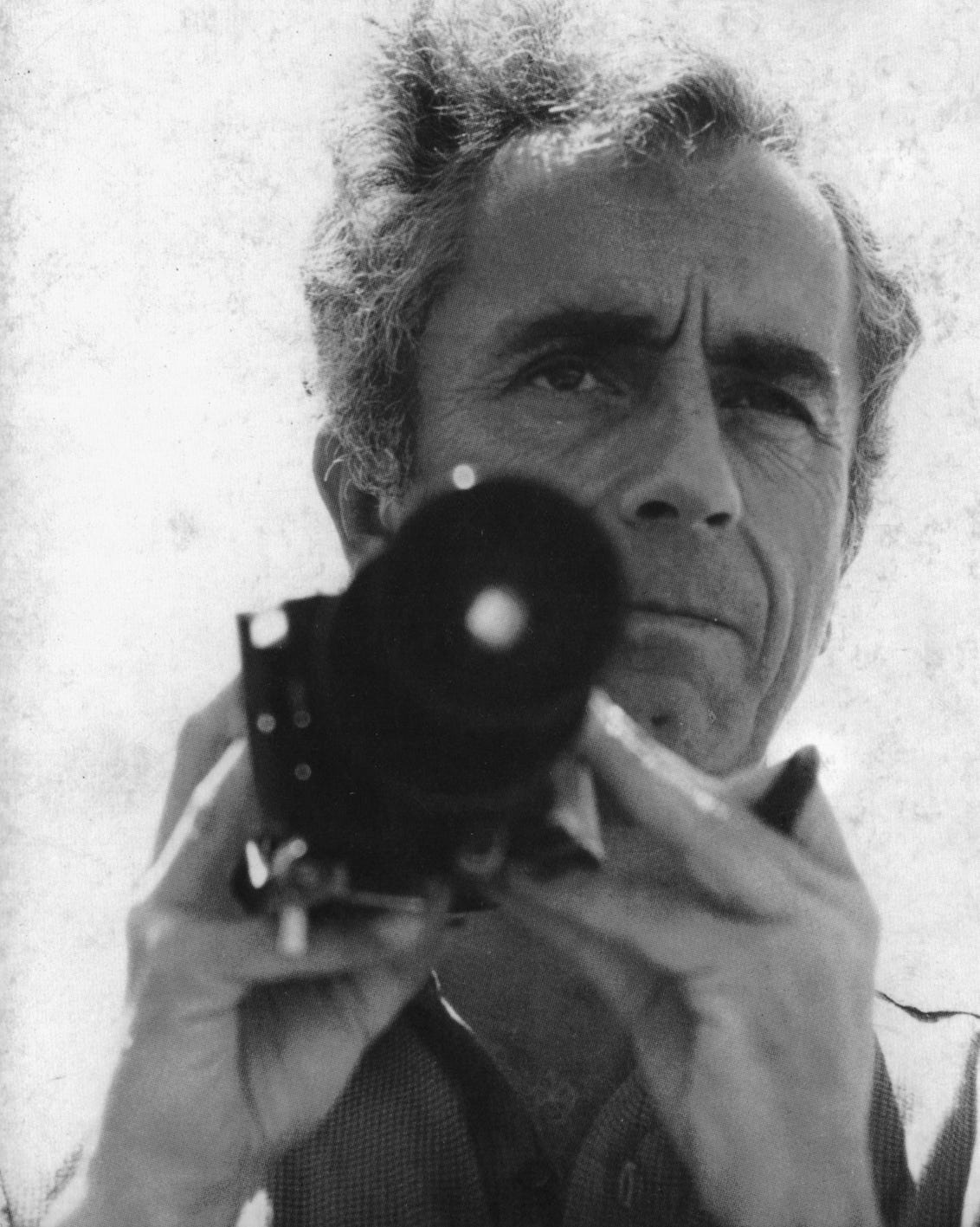

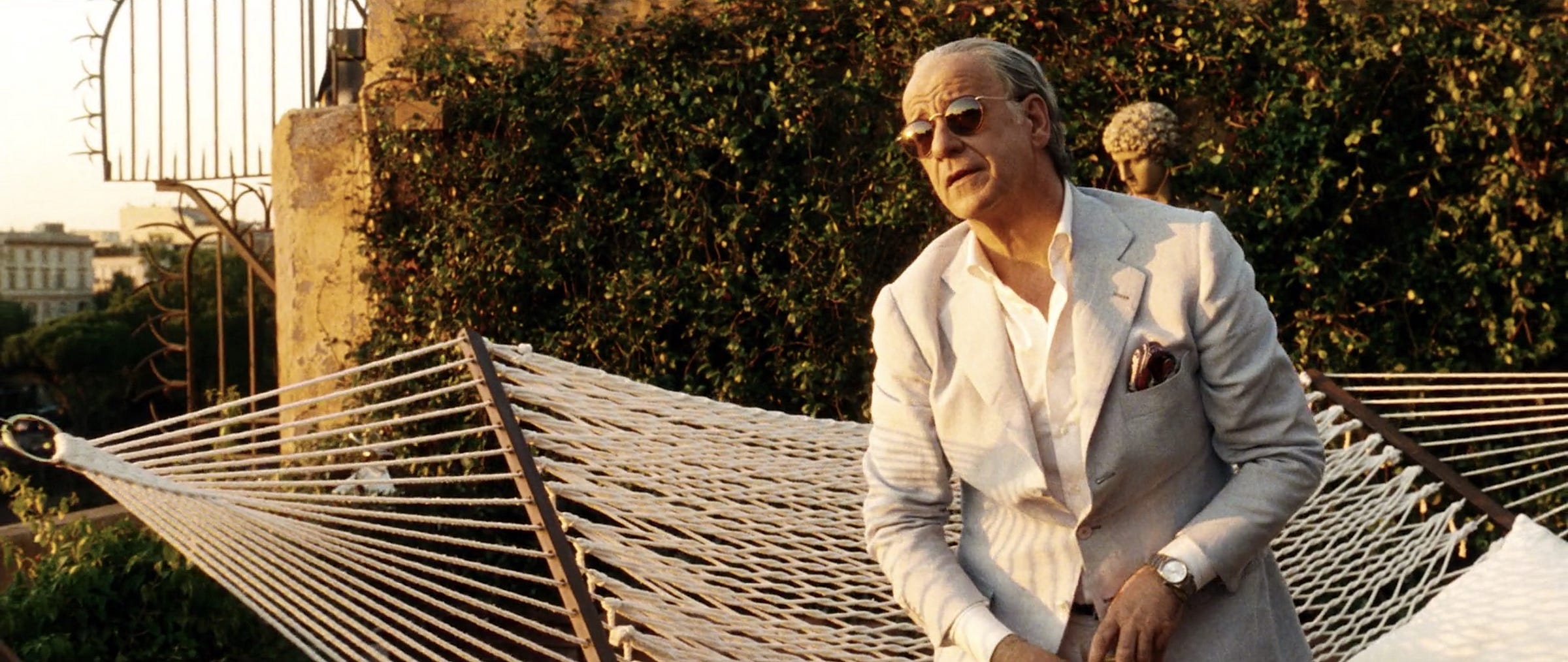

Michelangelo Antonioni — Existential Auteur

While post-war America spearheaded into consumerism and suburban optimism, continental Europe moved differently. There was no clean slate, no fantasy of reinvention. Instead, there was memory, decay, and the slow disintegration of the old world’s meanings. This is the world of Michelangelo Antonioni’s cinema.

Particularly in his iconic trilogy — L’Avventura, La Notte, and L’Eclisse — these films do not tell stories in the traditional sense. They dissect emotional topographies. In La Notte, we drift through Milan’s modernist buildings, glass towers, and bourgeois parties. The city is clean, elegant — and emotionally bankrupt. Relationships don’t break; they quietly expire. Architecture doesn’t serve as a container for meaning, but rather consumes it.

His characters, dressed immaculately, speak fluently — yet never touch. Not physically. Not spiritually. There is noise everywhere, but no communication.

And then comes L’Eclisse — perhaps the most haunting expression of modern disconnection ever filmed.

The romantic plot dissolves before it even begins. Rome is no longer the city of lovers, but a cold mechanism of finance, fashion, and empty routine. The stock exchange, once a symbol of future-building, becomes a grotesque ballet of greed. Even the light feels indifferent.

The film ends (spoiler alert) not with resolution, but with absence — a final montage where the characters never return. Only urban spaces remain, watching us with clinical detachment.

Modern cities, through Antonioni’s lens, are no longer places of memory or myth. They are places without a center. They have architecture, but no soul. Civilization, but no culture. Motion, but no meaning. His camera lingers not on action, but on the spaces between actions.

Modernism, for Michelangelo Antonioni, is the choreography of emotional disintegration — staged in sleek architecture, lit by artificial light, and orchestrated through silences that say more than language ever could.

Sofia Coppola — A Letter Lost in Translation

Now we move into the new millennium, when the world had become fully globalized — culturally intertwined, technologically hyper-connected… yet emotionally adrift. Endless cities, flights, hotels, screens — and a creeping sense that something vital is missing, even though everything is technically “fine.”

Lost in Translation is a film by the heiress of modern cinema, Sofia Coppola, that captures modern alienation not through tragedy or violence, but through soft dissonance. It tells the story of Bob (Bill Murray), an aging actor, and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), a young newlywed lost in early adulthood. They meet not in a romantic European alleyway, but in a sterile luxury hotel floating above Tokyo.

A city full of neon light, overwhelming pace, and impenetrable barriers.

They’re not tourists. They’re not locals. They’re ghosts with passports — caught between time zones and life stages.

Coppola doesn’t use Tokyo merely as a backdrop; she uses it as a metaphor. It’s ultra-modern, hyper-efficient, yet emotionally elusive. You can buy anything, experience everything — but touch nothing. The streets are flooded with light and noise, yet there’s no conversation.

In this way, Tokyo becomes the perfect mirror for early 21st-century modernism: the era of options without meaning. There’s no plot propulsion because there’s nothing to resolve. Only presence, mood, and quiet yearning. Her characters aren’t searching for answers — they’re just trying to feel something real.

At its core, the film explores the interiority of modern life — especially for those privileged enough to “have it all,” yet still feel numb. Coppola paints modern Tokyo not as dystopia or utopia, but as emotional purgatory — sleek, seductive, and slightly out of sync with the human heart.

Modernism, for Sofia Coppola, is the aesthetic of emotional detachment — ambient, beautiful, and gently suffocating.

Still — among all the criticism and negative worldviews many thinkers have projected onto modernity — we cannot deny that this is the reality we live in. There is no turning back to the old world anymore. The real question, ladies and gentlemen, is this: how do we enhance and experience the soul, the beauty, and the allure our cityscapes still have to offer?

The first thing we can empirically observe is architecture and landscape. While it’s true that I’m probably the last person in the room to speak in technical or intellectual architectural terms, I think we can all agree that these elements dictate the quality of life and aesthetic of the places we inhabit.

When you look closely, architecture is essentially a script for daily emotional reality. It dictates how humans move, see, feel — and even what we believe is possible. A well-designed city can slow your heartbeat, elevate your thoughts, invite connection, and make beauty feel like a birthright. A poorly designed one does the opposite: it alienates, exhausts, and flattens the soul. And it’s not just about buildings — it’s about the psychology of space, and how it shapes our quality of life, identity, and collective memory.

Try to imagine Paris for a second.

I won’t pretend I’m a native or that I lived there for decades — in fact, it was only a week-long visit. Less than one percent of what the city has to offer. Yet even in the 2020s, when large-scale buildings and new-millennium technologies have crawled into every aspect of life, people — both locals and discerning visitors — still walk into centuries-old palaces, sip coffee on historic streets, and live among Haussmannian architecture that absorbs modernity instead of being destroyed and replaced by it.

That decision alone makes Paris a beacon. A city that attracts tourists and maintains its myth — even though its actual daily life now contains many social issues we can all probably guess.

The same applies to Rome, Vienna, Kyoto, and other cities that radiate a kind of quiet magic — places that allow humanity to reconnect with themselves, with others, and with the environment in ways most modern metropolises fail to achieve.

But what about cities that were built to serve modernism directly? What choices remain for dense megacities driven by speed, capital, and fleeting lives? How can they allow people to truly live in them, not just physically exist on top of concrete?

I won’t pretend to offer an absolute answer. But from my experience walking through Bangkok over the past year — exploring far beyond shopping malls — I’ve realized that even here, there are spaces that make metropolitan life feel soulful and aesthetically livable. Spaces that remind people they are more than just bodies moving through systems of efficiency.

Take Bangkok Kunsthalle, for instance — a cultural hub in the old district of the city, renovated from a former industrial warehouse into a gathering place for creatives across disciplines. A space for connection, expression, and celebration of the human spirit in the modern age.

Or DIB Bangkok — arguably the city’s first true contemporary art museum. Featuring over a hundred artists from around the world, housed in a modernist space clearly influenced by Neo-Modernism and reminiscent of Tadao Ando’s architectural language.

These places ignite moments of calm and clarity amid skyscrapers and relentless pace. They are micro-restorations — done at the scale of streets, cafés, converted warehouses, and even empty lots. Intentional spaces that quietly resist the logic of the grid.

While the idea of visionary, sensitive political power reshaping cities at a grand scale is beautiful — the reality we’re heading toward is unlikely to look like that. The shift must happen at the micro level. Because even if many metropolises will never achieve the eternal myth Rome has accumulated over centuries, they can still enhance quality of life.

They can still remind us that mind, spirit, and connection can be nourished — even among millions of souls stacked in tall buildings, searching for something that feels like home.

Great piece, sir. Thank you for mentioning Hopper (one of my favorite painters; the other is O'Keeffe) and Lost in Translation (one of my favorite movies/soundtracks).

Loved this!