Confessions of an Independent Filmmaker

How I Building a Film, a World, and a Philosophy for Under $1,000

Why does someone need to make a film… I mean… why would this thing called a “motion picture,” constructed into a unified piece, need to exist in the first place? In the history of mankind, there have been countless attempts from humanity to express ideas, identities, and desires—things we cannot help but share with others. Story is how we understand the world, so, to be said, it’s the thing you and I are familiar with, using and receiving every moment of every day. And so, the idea of writing a manuscript, crafting literature, drawing, painting, sculpting, then “capturing a continuous frame” and turning it into a motion picture are all forms of expressing our ideas and identities to the world.

However, the format called “film,” especially when it becomes “cinema,” is something special—a multidimensional medium that contains “human” in a living form, one that breathes, cries, laughs, can love—then transmits that into our psychology, letting us experience it alongside the characters or whatever the director decides. It is the highest form of art—one that requires multidisciplinary study from individuals gathered into a single project, pouring hundreds of hours and thousands (or millions) of dimes into creating one.

But what if you (or myself, six months earlier) do not have that kind of resource? What if all you have is the idea—the calling in your heart that “this must be made into a film and shown to the world”? How would you start? What can you expect from the experience—one that offers no guarantee of clout, fame, or financial return, but instead a noble pursuit of staying in integrity with oneself?

Here are all the things—the auteur breakdown—of my first ever film: Metropolitan.

The idea of auteur theory was proposed as a critical concept that views the director as the primary creative force (the “author”) of a movie, imprinting their personal vision, style, and themes onto the work—much like a novelist does. In that sense, a director is the god of the film—who, most of the time, is also the writer. And writing, as a form of creation, will inevitably “insert” some part of the creator into the work, one way or another.

Think of Ian Fleming—the ex-British naval intelligence officer who became a legend by creating one of the most iconic characters and series of all time: James Bond 007. Look closely and you’ll see parts of Bond’s lifestyle—gambling, drinking, aristocratic gentlemanliness, naval background—are all reflections of Fleming. Moreover, he injected his post-WWII paradigm—the Cold War tension, the landscape of uncertainty—into the stories through various scenarios and villains. That said, I strongly believe that a screenplay or film must, in large part, exist with an auteur perspective and total direction. There is nothing wrong with telling the story one desires to tell, nothing wrong with placing oneself in the film as the protagonist—whether they act in it or not.

Metropolitan—when my DP, who happens to be my best friend for life, read the first draft of the screenplay, he instantly told me, “So this is basically your life and your lens of viewing the world?” Oui, monsieur. It is my story—one I experience every single day, again and again. And that is why this film needs to happen.

The idea of isolation and loneliness in a metropolis is not novel. Over the past century or two, many great thinkers and creators have orchestrated works of art that express their concerns and frustrations with modern life in their own ways. Charles Baudelaire with the flâneur archetype—a philosophical countermeasure to stay sane in modern Paris. Fritz Lang and Metropolis. Antonioni and his trilogy. Edward Hopper, who beautifully articulated the term “beautiful isolation” through his paintings. Metropolitan—this piece—is no different.

The initial idea was an accumulation of thoughts that occurred across many of my evenings in Bangkok. Being a connoisseur of sartorial elegance, mid-century jazz, and real-life conversation, the more I wandered through jazz bars, rooftops of five-star hotels, or dressed intentionally in a tailored jacket and pleated trousers, the more I thought: “The era is long gone.” No more Miles Davis, no more Dave Brubeck, no more Cary Grant, no more Audrey Hepburn. Those were fantasies of a bygone era—left for appreciation but almost impossible to find in the present. Jazz bars have turned into spectacle spaces for Instagram posts, where the intense solo of a saxophone becomes mere background noise. Five-star hotel bars no longer require proper footwear. And the evening life of people in the metropolis is far from civilization and elegance.

But what if there is a man who insists on staying true to the virtues he admires… even if he is the only one left doing so?

That is what Metropolitan is all about—a story of a man who keeps seeking, yet knows deeply that what he seeks is so little left to hold onto.

1. The Screenplay

Great writing will likely make a film great, but poor writing will certainly kill a film—no matter who directs or stars in it. What I mean by “poor writing” is not the presence of an unconventional storytelling structure or a vague, abstract narrative. I mean the simple fact that the writer is not aware of what kind of story he or she intends to tell.

I’m not a film student in the conventional sense, so the idea of creating a narrative based on structure, inserting subtle exposition, sequencing the arc—I’m far from fluent in those. But in Metropolitan, if there is one thing I am absolutely certain about, it is the unshakable element of purpose and intention behind the screenplay.

If the purpose of this film is to both challenge and convince the audience that elegance—no matter how alienated it has become—still retains its beauty, then everything from “Fade In” to “Fade Out” must orbit around that. And since this is essentially an autobiography of my own life, I understand best how to orchestrate place, time, and emotion in each scene to express this art.

The process began with the logline, the synopsis, and the first draft of the screenplay—all completed within a single week. Though several refinements followed before reaching the final version, the skeleton had fully formed.

2. The Location Scouting

This is the tricky part—especially for an independent filmmaker. Locations come with costs, particularly the commercially grand ones. There are four main private locations required: The Residence, The Cocktail Bar, The Jazz Lounge, and The Open Space Community Center.

With an estimated budget of less than one grand, privately renting these places was impossible. Moreover, for opulent locations like cocktail bars and jazz lounges, bringing in filming equipment is restricted unless—you guessed it—you rent and close the space for shooting.

Here was my play: with limited budget, what must be lean has to be lean, and human relationships play a huge part.

The Residence was provided by my best friend (who also happens to be the DP and the only crew member).

The Cocktail Bar and The Open Space Community Center could be approached with guerrilla shooting techniques.

The Jazz Lounge… thanks to my cocktail connoisseurship and charisma, I somehow received a referral from the head bartender to the owner, and was granted permission to film for a specific two-hour window—without having to close the place entirely.

It was a chaotic emotional roller-coaster, especially as the production schedule approached, but for better or worse, I got the locations I wanted.

3. The Cinematography

Once the screenplay and locations were settled, what remained was essentially the shot breakdown—the storyboard. Since this project is entirely my creation and fundamentally an auteur film, I needed a pair of eyes that understood my visual sensibility best. If you look at most of the published photographs of me, or my Instagram, they were all likely made possible by one man—my best friend and Director of Photography for Metropolitan: Mr. Got.

However, the “budget”—again, the villain of ambitious artists—played its part. He was not familiar with gimbals, and to shoot properly, he needed to buy one himself to pair with his existing single camera: the Sony A6300. Yes, this half-a-decade-old technology is what Metropolitan was shot on.

4K resolution, log profile—everything we needed, as long as it was paired with a stabilizer. We agreed on the DJI RS4 Mini. It was a heavy investment for him, especially if used for only one project. But his commitment to mastering the gear before shooting is something I truly respect. With our two main pieces of equipment and two additional lenses—35mm f/1.8 prime and 16–50mm tele—the shooting setup was ready.

What remained was the process of translating my screenplay into his vision. Though I suggested frames and shots, the DP’s eye was still crucial in determining whether a shot was possible and, if so, how to achieve it properly. The DP dictates which gear, lens, lighting, and shot sequence to use for each setup—though these need to be blocked in advance.

(For Metropolitan, all of this had already been completed during the location scouting phase.)

4. The Cast

Here comes the part that is perhaps the most interesting. For a long time, I debated with myself about why so many great auteurs—those who subtly proclaim themselves the gods of their own films—do not star in them. Only a few can do it: Orson Welles, Woody Allen, perhaps a handful of others. While the answer is still unclear even as I write this, it may be because being your own actor in your own auteur film removes the ability to hide behind the camera.

The actor is the body of the film—the one who portrays everything the director wants to appear on screen. And their job is only one thing: “Give the director what they want.” That is why many legendary directors have their own legendary actors: Hitchcock & Cary Grant, Fellini & Mastroianni, Melville & Delon, Scorsese & De Niro, Sorrentino & Servillo, and many more.

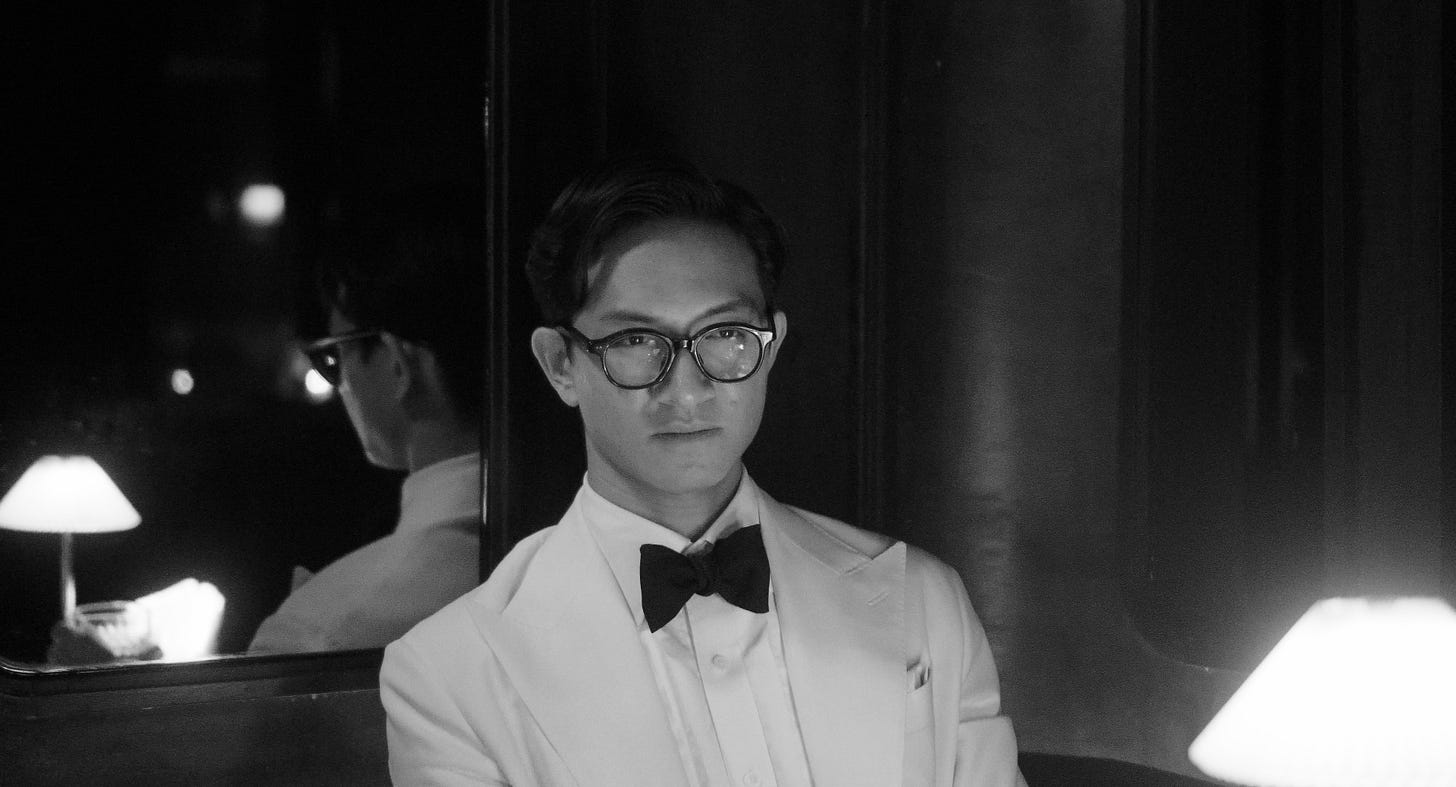

These actors gave their directors exactly what they wanted—and for Metropolitan, it is no different. The heart of this film rises and falls on a single character: The Man in the Ivory Tuxedo. The cast must be able to perform exactly what I want on screen—that he is at ease in a dinner jacket even if he is the only man wearing one in a metropolis of millions, that he appreciates the finer things in life, that he conveys the stoic, classical masculine gesture… and I could not think of anyone except Patrick Gunn—myself.

After the shoot, I realized how difficult it is for the director and lead actor to be the same person—especially when your entire crew is just a DP behind the camera with no assistant director. But to make this film complete in the way I desire, I believe I am the only one who could perform this role best.

What remained was the soulful element that would lift this film beyond vanity or a documented evening of a single man. The other essential character was the woman in the black dress. The purpose of this character is to help the audience—and the protagonist—realize that while his existence and values may be out of sync with the modern world, there is someone who appreciates them, even if she may not fully understand them. Her visual presence, elegance, and emotional projection I drew entirely from mid-century European cinema: Anna Karina, Françoise Dorléac, Monica Vitti…

With some luck and a referral from a close friend, I had the chance to audition a young lady—Sofi I. Schroeder. The moment I met her and watched her audition, I could sense that she was the woman in the black dress. The way she used language, her fluency in the language of cinema, and that gaze—one that perfectly matches the film’s climax—were undeniable.

Though her role appears in only two scenes and lasts less than 45 seconds, her presence completes Metropolitan exactly as I envisioned.

5. Editing

Of course, if the entire crew consists of me—writer, director, actor—and my friend as DP, then the editor cannot be far from either of us. And since this is an auteur-led film, I am the one who can orchestrate and perform the narration best.

If you have ever edited a YouTube video or made a film, you know this process is the most draining and time-consuming. Selecting shots, determining pacing, designing sound, color grading, sometimes adding VFX… In total, 32 hours were spent completing Metropolitan’s post-production in the Adobe ecosystem. (It could have been 28, but Premiere Pro crashed once, and I had to reapply stabilizer and remove noise again in After Effects.)

But after a week of depleted energy, when the scheduled date arrived, I finished it—screened it privately to my DP and a few discerning eyes. Then I submitted it to the only destination I dedicated myself to: Clermont-Ferrand—the Festival de Cannes of short films.

And the result? As announced a week ago while I’m writing this—among approximately 8,900 films submitted this year, Metropolitan did not qualify for screening.

I don’t know if this should be surprising or not—to make the first film of my life with less than a $1K budget, with only one crew member, and hope to have it screened at the biggest short film festival in the world. The feeling when I learned the result was far from devastating—but certainly not pleasant. It drove me to think about what could have been better: better acting, better shot framing, better writing…

But I cannot rewind this film anymore. It is a chapter that has ended, and in some way, it has fulfilled its purpose. Initially, my main intention in making Metropolitan was to express my worldview—how elegance, though lost and unknown in the modern day, can still be beautiful. Through thoughtful rituals, stillness of moments, and self-awareness of who you are—without compromising those values.

This piece, I believe, is the manifestation of auteur theory at its finest. A film made and directed through a single mind. And in the end—whether viewers think it is good or bad—it tells the truth of my own self in the format I consider deeply sophisticated.

It is not a perfect film—far from it—but every flaw is a lesson that will not repeat in the next one.

You will be able to see Metropolitan on December 21st, 2025.

I will post an update when the time comes.