Modern Times, Antonioni’s Way

A trilogy of disconnection that defined the 1960s and quietly defines us still.

When one watches a film, they either understand it or they do not.

The modern film industry has turned this medium increasingly into a channel of entertainment, designed to make every dime spent worth it by giving audiences exactly what they want. In most cases, the masses crave a surge of excitement, the joy of adventure, the ideal of romance on screen.

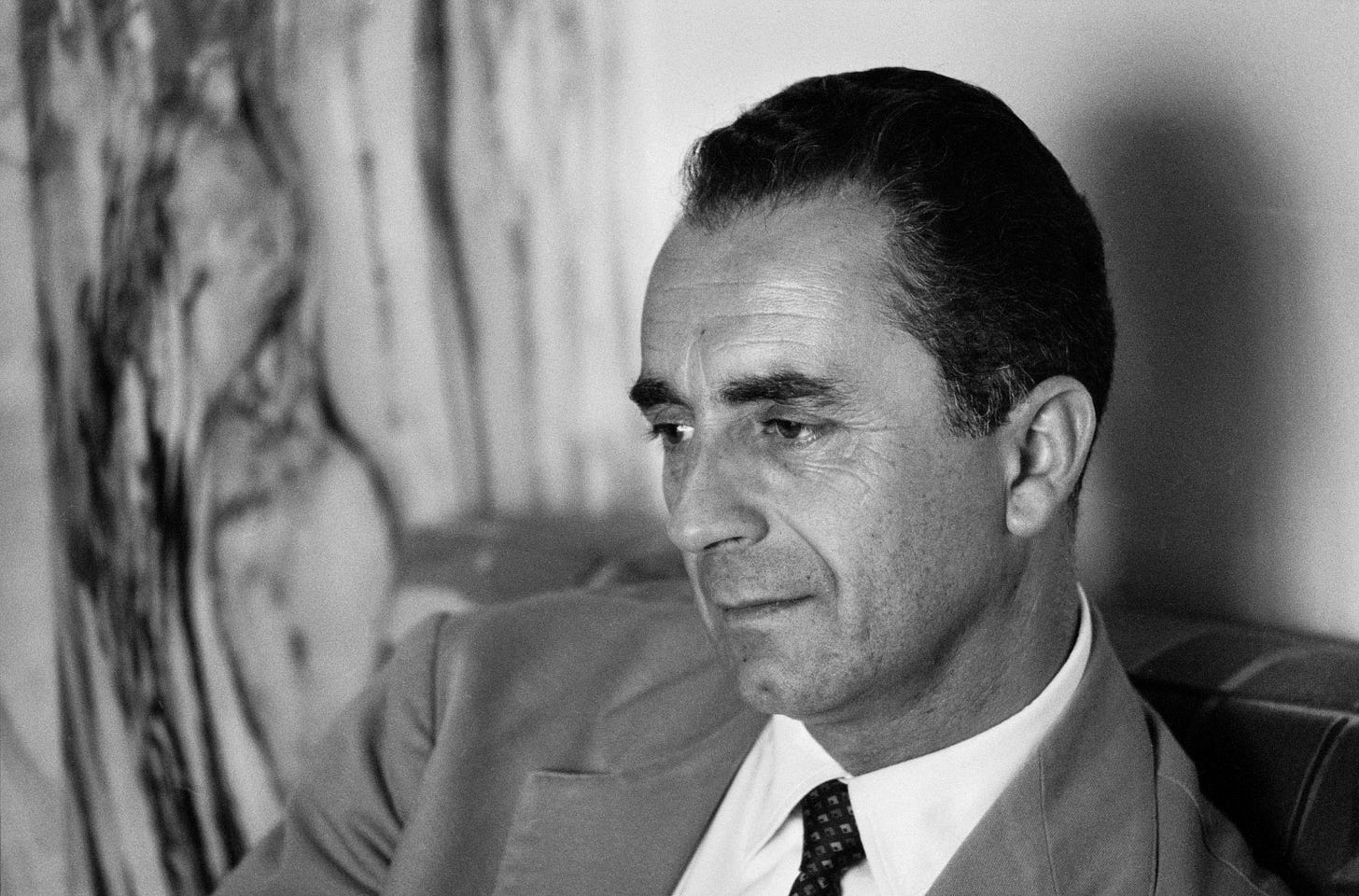

But that was not the case in the mid-century, particularly on the Continent, when directors embraced the ideology of the auteur: the “god of their own film,” possessing complete artistic control over their vision. It was an era when filmmakers did not hesitate to express what they thought through what they saw on the silver screen. Among those great names stands the maestro Michelangelo Antonioni. Internationally recognized for his first English-language film Blow-Up (1967), he was already revered among cinephiles as the auteur who questioned and portrayed the hollowness of modern life in the face of existential crisis.

Born into a bourgeois family in Emilia-Romagna, Italy, Antonioni cultivated his artistic sensibility through music, architecture, and painting. During his formative years, he moved through several passages that honed his eye, his language, and his grasp of cinematic reality: writing screenplays while at the University of Bologna, and later working as a film critic after moving to Rome. There, he briefly attended the prestigious Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, arguably one of the finest film schools in the world, where he mastered the technical side of filmmaking.

From there, Antonioni rode the wave of Neorealismo, a movement that explored the struggles of post-war life, often collaborating with figures such as Roberto Rossellini. As the new decade dawned, he shifted his focus. His first feature, Cronaca di un amore (1951), marked a departure from the plight of the poor toward the world he knew best, the bourgeois. The film, a noir-inflected tale of infidelity and moral decay, became his statement of intent. Here, Antonioni began his true auteurship, dissecting the absurdities of the carefree social class, a theme he would master in his celebrated trilogy, all starring his muse and love, Signora Monica Vitti.

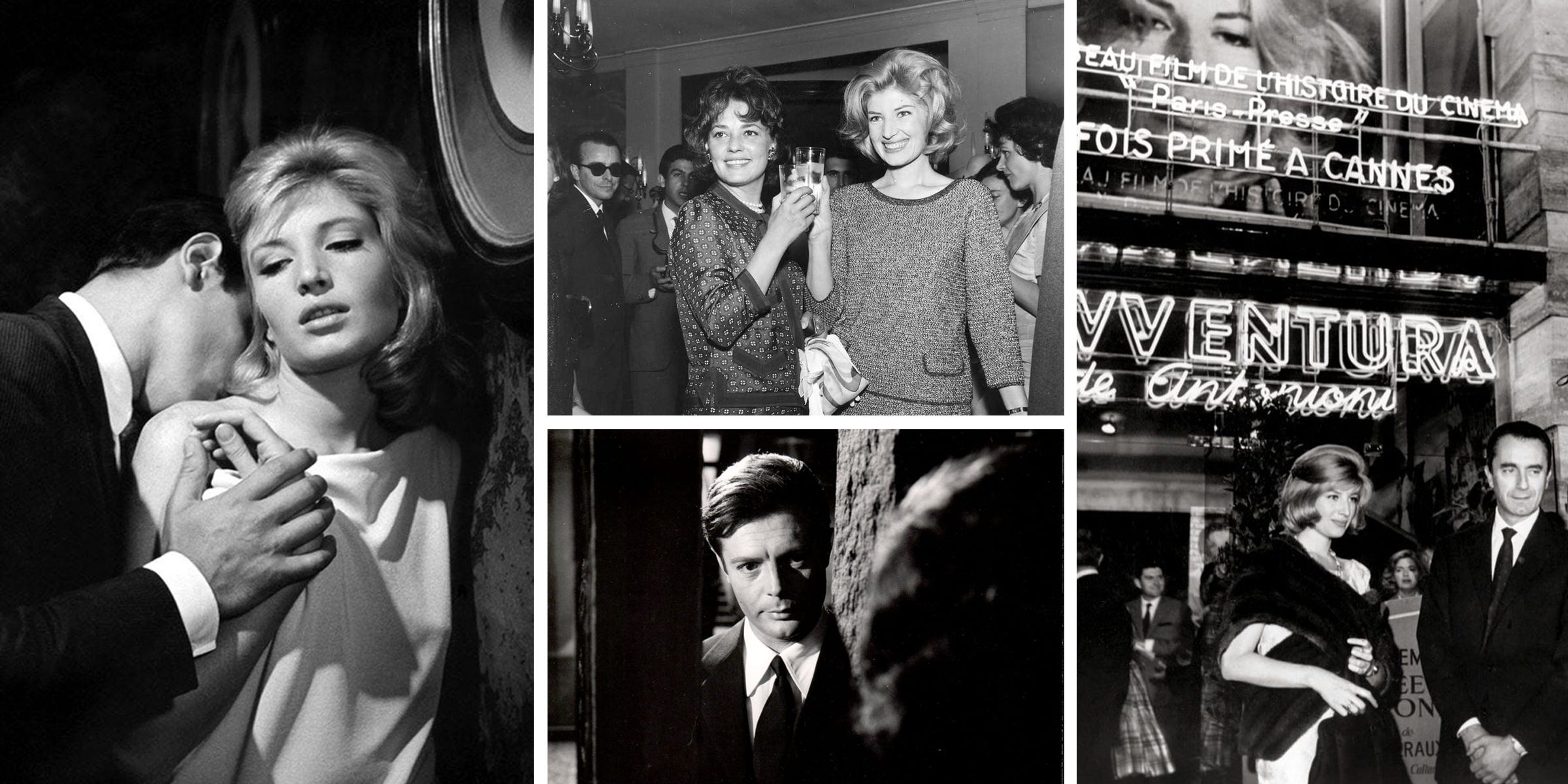

The first of the trilogy, L’Avventura, premiered at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival and initially met a storm of disapproval. Audiences booed, some laughed, and Monica Vitti, humiliated, reportedly fled the theater in tears. Yet within days, critics reappraised it as “the best film at Cannes” and “a statement on the melancholy of modern times.” Antonioni had constructed something radical. He treated plot not as the vessel of meaning but as a pretext, a way to explore emptiness, spatial disconnection, and the failure of narrative itself. It was a deliberate aesthetic rebellion against cinematic expectation.

At its core, L’Avventura begins as a story of disappearance: Claudia (Monica Vitti) and Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) set out to search for Anna (Lea Massari), who vanishes during a yacht trip off the coast of Sicily. What unfolds is not mystery but metaphysical drift: boredom, jealousy, tension, and desire, all expressed through Vitti’s mesmerizing restraint. Antonioni extends every moment, pares dialogue to its essence, and lets silence articulate what words cannot. The result is not a film about finding the missing but about confronting the emptiness that remains when stimulation and desire fade away.

Of the three, La Notte is perhaps the most complete. Not necessarily the best, but the one in which Antonioni orchestrates world, narrative, and emotion with the most harmony, bringing it all to rest with that haunting final scene between Giovanni (Marcello Mastroianni) and Lidia (Jeanne Moreau) in the villa’s empty golf course. Its excellence was affirmed by the Golden Bear at the 1961 Berlin Film Festival.

Far from the coastal openness of L’Avventura, La Notte confines itself to the metropolis of Milan, a city symbolizing modernity, capitalist ambition, and spiritual decay. Here, Antonioni paints his vision of the urban soul: architectural rigidity, emotional sterility, and the slow erosion of intimacy. The marriage of the Pontanos is lifeless; joy appears only once or twice throughout the film. Antonioni asks, What happens to those who already have everything society tells them to desire? His answer is emptiness, in love, in ambition, in being. When Valentina (Monica Vitti), the intelligent and introspective heiress, enters the story, she momentarily revives Giovanni’s fading spirit. She represents youth, vitality, the illusion of renewal. Yet Antonioni’s verdict is merciless: even in youth, alienation persists. By the end, the night fades but the emptiness remains.

“Abstraction” is the word that defines L’Eclisse, the most philosophical of the trilogy. Here, Antonioni’s psyche is projected through the vast avenues of suburban Rome, through the crowded din of the stock exchange, and through two people: a woman who no longer knows how to love, and a man who no longer knows what he wants. The film is not driven by plot but by rhythm, by fragments of gesture, light, and silence that pose the question, What remains of meaning when human presence dissolves into form, rhythm, and space?

At the center are Vittoria (Monica Vitti) and Piero (Alain Delon). Their connection flickers between curiosity and disillusionment. She is introspective, almost self-dissolving; he is restless, materialistic, tethered to the abstract world of capital. They circle each other like symbols of two exhausted poles of modern life. The final sequence, when Antonioni removes the human altogether, remains one of cinema’s most radical gestures. The world continues: lampposts, puddles, wind, passersby. Humanity vanishes, but the motion of existence persists. Here, Antonioni transcends storytelling to think through cinema itself, using rhythm, architecture, and absence as philosophical language.

Across these three films, Antonioni sculpted an elegy of existence, a study of the modern soul adrift in a post-war Europe where a single conflict could shatter serenity, and where modernity itself made human connection increasingly impossible. Through industrial landscapes and bourgeois elegance, through ennui and alienation, he revealed the fragility of being, without overt drama, but with the subtle intensity of Monica Vitti’s gaze.

His trilogy remains a mirror of our own condition: elegant, uncertain, and quietly haunted by the question that still lingers,

What, if anything, remains when the noise of life fades away?

If you don’t love these films you are decidedly not cool.