Narrative Capital: The Secret Behind Icons

The One Asset Every Legend, Billionaire, and Cultural Giant Shares

In the last essay, I teased a little about the term Narrative Capital.

When people think of the word capital, their minds usually jump to either a big city — the ideological core of a nation — or to “money,” the asset that plays the main role in their lives.

(Unfortunately, most of the time, people don’t have a great relationship with this “player”.)

If we look at the root of the word capital in Latin, we find that it comes from caput, meaning “head.” In Latin, this could refer not only to the literal head but also to something chief, principal, or of primary importance.

It’s this interpretation that branched in different directions: a capital city was the “head” city of a region, the seat of authority; a capital letter was the “head” or principal letter in writing; and in finance, capital grew from the idea of “heads” of cattle, since livestock was an early measure of wealth.

Over time, the term shifted to mean a principal sum of money or assets that could generate profit, much like a herd produces offspring. From this root meaning of “head,” capital came to denote leadership, prominence, and essentially the resources that form the foundation for growth.

And what you’re going to discover in this weekly piece is that foundation for growth — the core ideology of capital — extends far beyond just a metropolis or money. It exists in a story, a myth — in the very narrative of an entity, of a being. The one who accumulates, or even consecrates, this capital will experience life on an entirely different echelon than those who ignore it — in the name of Narrative Capital.

The Universal Law of Human Nature (And How It Shaped Society)

First, you need to understand a few fundamentals of human nature that directly connect to the term narrative — a spoken or written account of connected events (AKA a story). It is the universal law that dictates everything you live, see, and experience today.

Though I explored much of this — especially in the realm of perception — in the last essay, this time we’re going bigger and wider.

On a micro scale, you, as a human, always understand things in the format of a story. When someone tells you something like:

“Listen, I’ve got something exciting to share. Last night, I did this, I faced that, then this happened, and the consequences were this and that…”

Your mind immediately organizes it as a narrative. Even in something as simple as appearance, the same mechanism applies. For example, right now I’m sitting in a café where the barista has a nose piercing. Instantly, my subconscious begins spinning a story: she must be this kind of person, with that kind of behavior, holding a certain character. My mind associates the accessory with a meaning — in other words, a story of its own.

Why?

Two reasons:

Humans are lazy. We love shortcuts. We want to make sense of things as fast as possible. (Thanks to this instinct, our ancestors survived instead of becoming dinner for saber-toothed tigers.)

Story is a package — a bundle of information threaded together that delivers an exact emotion and consequence with maximum efficiency.

And if this works on a micro level — embedded in every human being — it also applies when things scale up: when humans gather, from tribes to full societies.

“Man is by nature a social animal; an individual who is unsocial naturally and not accidentally is either beneath our notice or more than human. Society is something in nature that precedes the individual. Anyone who either cannot lead the common life or is so self-sufficient as not to need to, and therefore does not partake of society, is either a beast or a god.” — Aristotle

Today, individualism has become the norm. Many disguise their inability to form real-life social connections as being introverted. Worse, the internet often romanticizes the idea of being a lone wolf and independent.

But here’s what they cannot deny: humans long for connection.

They long to belong to a place, a society, a circle that erases their loneliness. And in the history of humankind, we’ve categorized this formation of collectiveness as culture — the manifestation of human intellectual achievement, regarded collectively.

“In the world there is, parallel to the force of death and constraint, an enormous force of persuasion that is called culture.” — Albert Camus

Mass perception sees culture as something abstract — intangible, with no “return on investment.” People think of art, cuisine, history, as luxuries: nice to have once life’s material needs (food, shelter, status symbols) are secured.

But if we look at it through the lens of Maslow’s Hierarchy, culture doesn’t just show up at the top in self-actualization. Culture has been present since Stage 2 — safety — and continues through belonging and esteem.

Stage 2 (Safety): From earthquake-resistant homes in Japan to traditional medicine in households — safety itself is culturally defined, not purely biological.

Stage 3 (Belonging): Rituals, gatherings, festivals, communal meals — all turn social contact into a deeper sense of belonging.

Stage 4 (Esteem): Luxury goods, academic titles, ceremonial roles — all transform esteem into cultural recognition rooted in shared values.

So, how do culture and narrative connect?

Here’s the bridge.

Culture is largely formed and sustained through the stories people tell. Narratives give abstract values and practices shared meaning. Myths, religions, national histories, even your friend’s casual jokes — they all transform actions into expressions of collective identity.

Stories carry values across generations, ensuring traditions don’t become empty rituals but remain anchored in why they matter. At the same time, narratives provide identity and belonging, telling people who they are and where they fit. Just like nations build themselves on founding myths, ancestral legends, or community stories that reinforce the “we” binding individuals together.

In this way, narrative isn’t just a reflection of culture — it is the very fabric weaving culture itself, giving coherence, continuity, and meaning to human life.

Basically, narrative is the gateway to belonging — to being part of something bigger than the individual, bigger than the singularity of one’s own life.

And here’s the key: outside of religion and nations, one other realm leverages narrative and culture at their finest — business (the engine of capitalism).

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” — Adam Smith

On the surface, capitalism is often seen as a school of thought, an economic system that, since the birth of modernity, has been widely adopted and now runs the world. (Even political systems that favor communism, like the Republic of China, still worship capitalism as their engine of domination.)

The reason is simple: capitalism reflects human nature.

At its core, capitalism is about exchange, accumulation, and the pursuit of self-interest — all of which mirror the most primal aspects of human behavior:

securing resources

trading what we have for what we lack

improving our standing in the group

This existed long before capitalism became an “economic system.” Bartering, competition, and innovation have always been part of human communities. Capitalism is simply a structured extension of natural human tendencies: the drive to survive, to improve one’s conditions, and to gain recognition through material or symbolic wealth.

So, if both culture and capitalism are rooted in human nature, would it surprise you that the two are directly correlated?

If culture is the gateway through which individuals form collective identity — and capitalism is the act of exchanging value — then business (the institution that systematically distributes value) inevitably becomes the creator of culture for specific groups of people to belong to.

Consider these iconic businesses:

Apple turned a technological product into a cultural ritual. Every iPhone launch isn’t just about specs; it’s about belonging to a global tribe that associates itself with innovation, status, and minimalist aesthetics.

Ralph Lauren transformed a little polo pony logo into more than fabric branding; it represents aspiration, class, and timeless style. People don’t buy Ralph Lauren just for clothing utility (in my sartorial experience, their pique cotton isn’t worth more than $30–40, given it’s mass-produced in China). What they buy into is the story of sophistication and social standing.

Starbucks doesn’t primarily sell coffee (many argue it’s average at best). What it sells is a cultural experience: the branded cup, the personalized order, the “third place” between home and work. It created rituals people return to again and again.

Of course, these three are the classic examples — ones you’ve probably seen dissected a hundred times in marketing sites, brand case studies, or by internet gurus talking about “the secret of success.”

But here’s the real insight: when narrative is leveraged at its finest, it goes beyond billions in capitalism, beyond cultural creation. Narrative becomes an asset — one that multiplies everything in your life.

Why Cultural Billionaires Embrace Sartorial Elegance

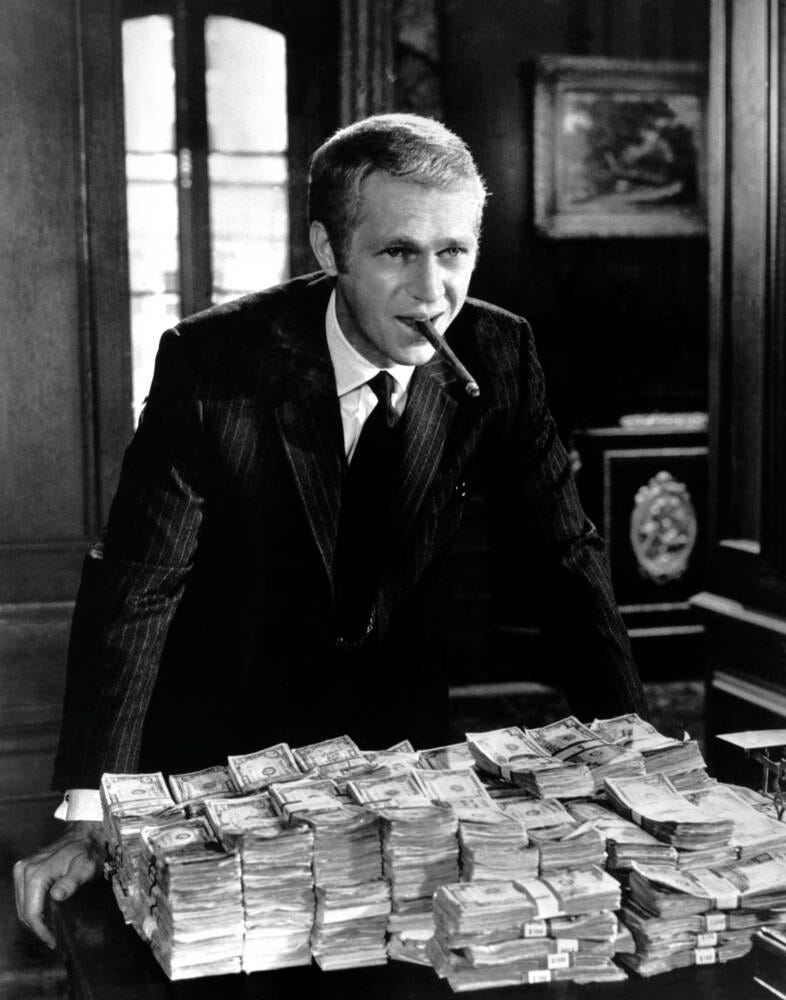

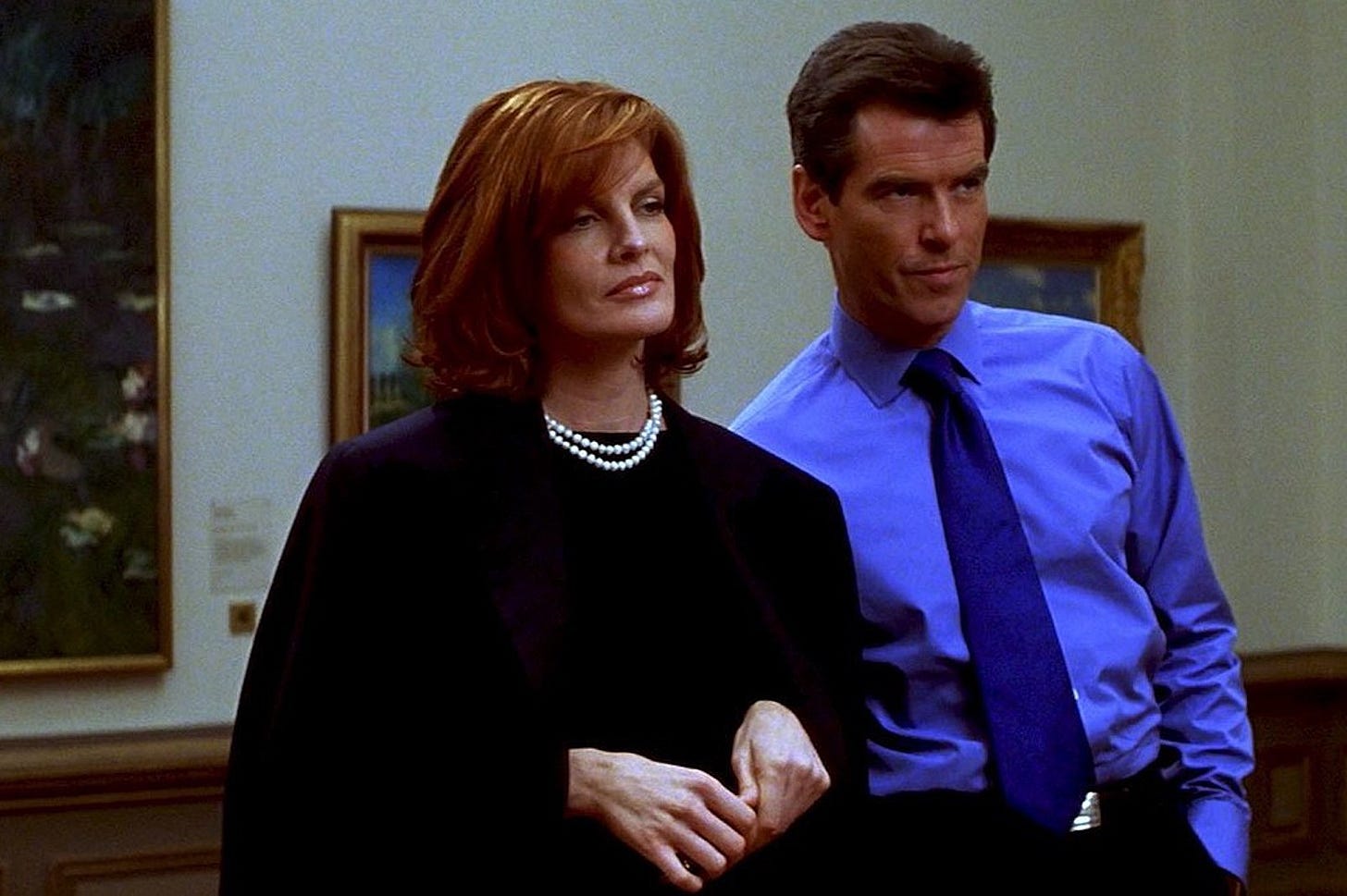

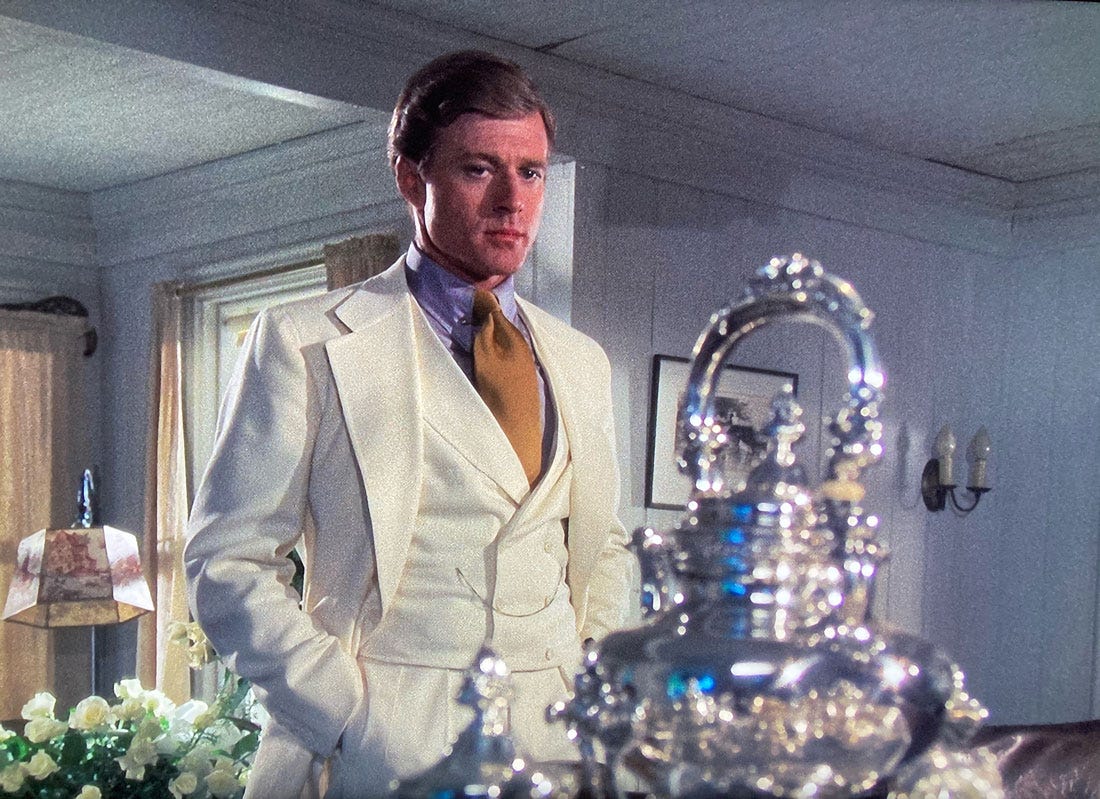

When it comes to pop culture — especially cinema — several iconic characters immediately come to mind when we think of the sophisticated, suave, debonair millionaire (or billionaire) archetype:

Bruce Wayne (especially Christian Bale in Nolan’s trilogy)

Thomas Crown (both Steve McQueen and Pierce Brosnan’s versions)

Robert Redford in his deadly elegant gentleman roles like Gatsby or John Gage (Indecent Proposal)

And, more recently, Matthew McConaughey in Guy Ritchie’s The Gentlemen

While each of them has their own uniqueness, personality, and inner tension, they all share three things in common: money, cultural flair, and sartorial elegance.

And this is no coincidence. (I’ve covered this in detail in my essay on the power of clothes and reality perception.)

For these on-screen icons, style is not just fabric — it’s the visual embodiment of nobility, the fantasy of being the most complete man alive. Their clothes convey class, status, and elegance without a single word spoken. Just by appearing on screen, their garments shape the perception of others — both within the film and in the audience’s imagination.

This creates a narrative of its own, anchored in universal virtues like poise, confidence, intellect, charm, mystery, and independence.

For instance:

Thomas Crown — “The Reckless Refinement.” From McQueen’s glen plaid three-piece suits to Brosnan’s midnight-blue ensemble (shirt and tie in the same tonal shade), his wardrobe reveals a man who treats life like a chess match — polished, daring, and always one move ahead.

Robert Redford — the Romantic Gentleman. From Gatsby’s cream lightweight wool suits to John Gage’s impeccably cut navy stripes, his style expresses generosity and allure. His wardrobe presents wealth not as dominance, but as a tool for creating beauty.

The narratives they radiate through style bend the world to their will — shaping how others think of them, and how they act in response to that perception.

What’s beautiful is how different they are from one another, even though they embody the same category of virtues. This difference comes from the myth and meaning at the core of the narratives they project.

Bruce Wayne and Thomas Crown may share the same enterprise-owner archetype — men who control entire buildings in Manhattan — yet they are remembered in strikingly different ways. Likewise, Redford’s Gatsby and McConaughey’s character in The Gentlemen both operate in underground business landscapes, but their style reflects entirely distinct identities they project and embody.

Why? Because each of them carries a unique idea, vision, and meaning to stand for in life. And that meaning is reflected in their narrative.

It’s that narrative — the one they own uniquely, unlike any other millionaire or billionaire — that gives them leverage money alone can never buy.

The ultimate reward: Being remembered for everything they do.

By now, you already understand how essential perception is in human life — the ability to control, bend, or even manipulate it in your favor is immeasurable.

When we combine Narrative (the form of story) and Capital (the head of an entity, the foundation of growth), we get:

Narrative Capital = The Engine of Growth in the Form of Story.

It lives in perception. It is the cultural gravity that pulls people toward an entity and keeps them there. It is what makes an entity feel inevitable. And it compounds: the more people believe the story, the more valuable the entity becomes.

This isn’t theory — it’s the law of human nature. It’s the universal truth behind the grandest acts: from a man in a black turtleneck hypnotizing the world with an idea and a square electronic device… to the tragedies of historical wars that always began with a narrative.

When you decide to accumulate this capital in your life, everything you do multiplies — from the words you speak and ideas you share, to the value you distribute in the capitalist economy.

And if you’re wondering what the components of Narrative Capital are, here’s the formula:

NC = Myth × Meaning × Perception ÷ Commodity

Myth — The irreplaceable story that cannot be swapped with another.

Meaning — The philosophy that transcends an entity’s own benefit.

Perception — The collective belief reflected back by society.

Commodity — The forces of sameness, quantitative inputs anyone can copy.

Let’s break it down with two examples — one fictional, one real.

Thomas Crown

Myth: A billionaire who steals not for money, but for mastery. A man who outgrows reality and rewrites it. His story isn’t interchangeable; it’s a singular legend of elegance, rebellion, and precision. He is the author of his own storyline — answering to no one.

Meaning: Freedom is the only true wealth. Every move critiques conformity and glorifies sovereignty. He’s not chasing success — he’s redefining it.

Perception: To the world, he embodies seductive power — admired, envied, untouchable. People don’t just believe in him; they aspire through him. Belief gathers around his myth like gravity, bending reality in his favor.

Commodity: He is unscalable by design. No features, no pitch, no comparison. Too rare to be sold, too sovereign to be copied. The luxury of originality.

And that’s why, while countless characters may resemble him, none hold his unique position as the connoisseur of sovereignty.

Elon Musk

Myth: The man who dares to colonize Mars, build AI, electrify cars, and troll Twitter (aka X) like a teenager with a death wish. His myth is raw, unpredictable, unreplicable — an attempt to rewrite history itself.

Meaning: Powered by a mission: extend human consciousness beyond Earth. Every company he builds is an existential bet, a physical manifestation of his values — energy, intelligence, freedom, survival.

Perception: Society doesn’t just follow Musk — it reacts to him. Love or hate, believe or mock, he lives rent-free in the cultural psyche. Proof that one obsessed mind can bend reality. Terrifying, magnetic, inevitable.

Commodity: Musk is chaos. Volatile, polarizing, never bland. He doesn’t optimize — he escalates. While others polish, he launches rockets and tweets memes in the fallout. (Which, inevitably, led to Tesla’s irrational but exponential decade-long growth — chaotic like Musk, exponential like Musk.)

If you want to see Narrative Capital at its finest — through existential, capitalist, and cultural lenses — Elon Musk personifies it.

The question then becomes:

How do you build and accumulate your own Narrative Capital?

Look deeply into each component of the equation: myth, meaning, perception, commodities.

Myth: You already sit on it. It’s buried in your psyche. You just haven’t dug deep enough or dared to tell it to the world. Ask yourself: Stripped of job, degree, possessions — who am I? Who do I want to become? Sit with it long enough, and the answer will emerge.

Meaning: Your purpose. The reason you exist beyond personal gain. It ensures your myth resonates with others and makes them irresistibly drawn to you.

Perception: The way others experience you — through how you speak, dress, walk, and present yourself. Many dismiss these as superficial, but they are the very things shaping memory, emotion, and belief about you. Optimize them, and reality will bend in your favor.

Commodity: The sameness you must avoid. Degrees (even Ivy or Oxbridge), job titles, jargon, features, prices, efficiency — these are things anyone can replicate. They make you indistinguishable.

Your job, gentlemen, is simple: cultivate M × M × P and minimize C.

Do that, and you will own Narrative Capital — the multiplier of everything you do. Whether it’s being remembered in your social circle, influencing society, or achieving 10–100x growth in the economy, the principle holds.

That’s all for this essay.

Au revoir.