The True Meaning of Cinema

It has always been more than entertainment

Movies… the medium that has traveled a long journey from its origin. From a series of still images laid one after another, frame by frame — to a full canvas where a human can brushstroke any idea and turn it into motion picture.

For over a century, movies (or films) have left plenty of iconic cultural marks on mankind — from philosophy to fashion to aspiration. Which is why it’s quite sad to see so many of those marks disappearing from the modern landscape of cinema.

If you’re a regular movie watcher and not a “cinephile” (who, from the casual watcher’s perspective, seem unnecessarily obsessed with the substance of every film they watch) — you’ve probably noticed that the movies appealing to you are either superhero films, blockbuster pieces, or adaptations of pop culture material…

Now, I don’t want to sound like a purist critic who talks down to those motion pictures, since they certainly have their reasons to exist in the first place.

“Much initiative in linking gratification and media choice lies with the audience member.” — Elihu Katz, Jay G. Blumler & Michael Gurevitch (Uses & Gratifications framework)

That’s the gold standard of thought in how media functions in society: to reflect the current culture and feed people whatever they desire.

In the new millennium, where “casualness” has become a kind of doctrine for most people — the content, the message, the things they consume must also carry that same sense.

However, I also cannot deny that it’s a shame to see cinema turned into a “circus.” (Yes, I agree with many old-school filmmakers who believe modern movies function like a circus: greatly entertaining, but easily forgotten.)

Because, ladies and gentlemen, this word — cinema — stands for something far deeper and more substantial than the surface of a top-20 blockbuster list each year.

It’s a seductive dose of ideas, a mirage of aspiration, the selfishness of humanity, and a whole world that gives perspective on that thing we call “life.”

All of which you can see during the Golden Decade of Cinema.

1960s: The (True) Golden Age of Cinema

Some of you might be familiar with the “Golden Age of Hollywood.” If not, it refers to the period during the 1930s–1950s — the era when Hollywood reigned supreme as the biggest industry of filmmaking.

There were two main factors that contributed to its status:

Obsessive control — from the birth of the Hays Code, which shaped the way films were made, to the advancement of the studio system that could churn out plenty of films in a single month, to the image manipulation they had over the stars of the era.

The illusion of glamour — which turned ordinary actors and actresses into gods and goddesses in the eyes of the audience. They created myths, aspirations, ideals of character, and societal norms that leaned toward elegance and conservatism.

While there were plenty of genres and dynamics in this period — from Fred & Ginger musicals, to screwball romantic comedies, to film noir thrillers, to dramatic screenplays — they all relied on predictability, a specific frame of creation, and repetitive templates.

But that all changed when the New Wave of filmmakers from the continent decided to go against everything Hollywood stood for at the time, and turned cinema into something greater than just a medium of reflection and manipulation.

“After Breathless, anything artistic appeared possible in the cinema.” — Richard Brody on Jean-Luc Godard

Before the 1960s, there had always been experiments in filmmaking that set themselves apart from typical Hollywood. For example, Italian Neorealism embraced reality with true locations and non-actors, while Japanese Post-War cinema dove deep into politics with unconventional pacing and storytelling. But those movements were still just niche undercurrents.

When the 60s arrived, all of those experiments fully shaped the idea of movies into cinema. They stopped being just mass-manufactured products for entertainment and began to be widely accepted — by critics, filmmakers, and audiences alike — as an art form on par with literature, painting, and theater.

A Spiritual Channeling Wrapped in Seduction

“The artist is always the servant, and is perpetually trying to pay for the gift that has been given to him as if by miracle.” — Andrei Tarkovski

The most empirical evidence of this can be found within these iconic cinematic pieces by great auteurs.

Federico Fellini — The Magician Who Blurred Realism

If you’re a cinema lover, you’ve probably heard of La Dolce Vita (even if you’re not, chances are you’ve still heard of it). The term itself has become shorthand for the lifestyle of Italians in the mid–20th century. When people think of it, the images are clear: an Italian uomo in soft tailoring, riding a Vespa with the Colosseum in the background, or a donna with sharp eyeliner, wearing a Dior New Look silhouette, sipping coffee with a cigarette in hand.

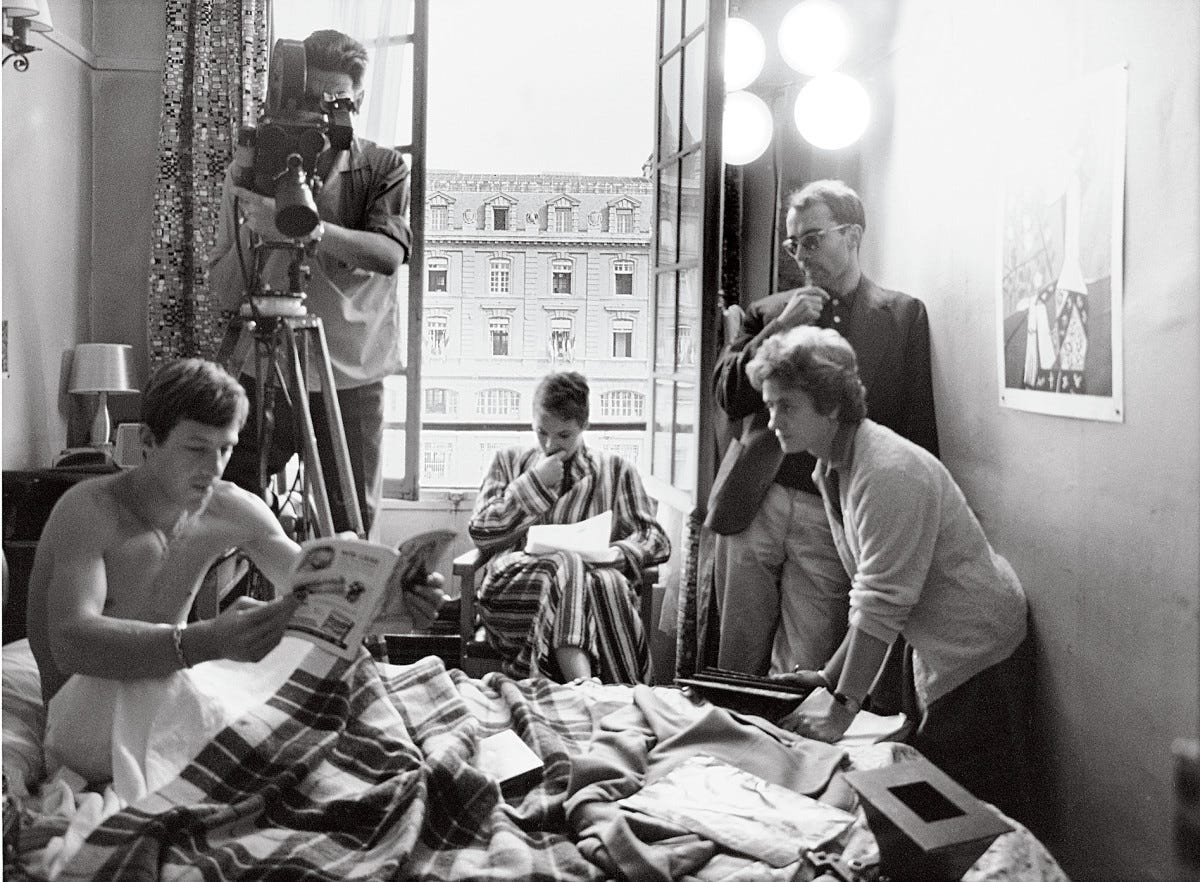

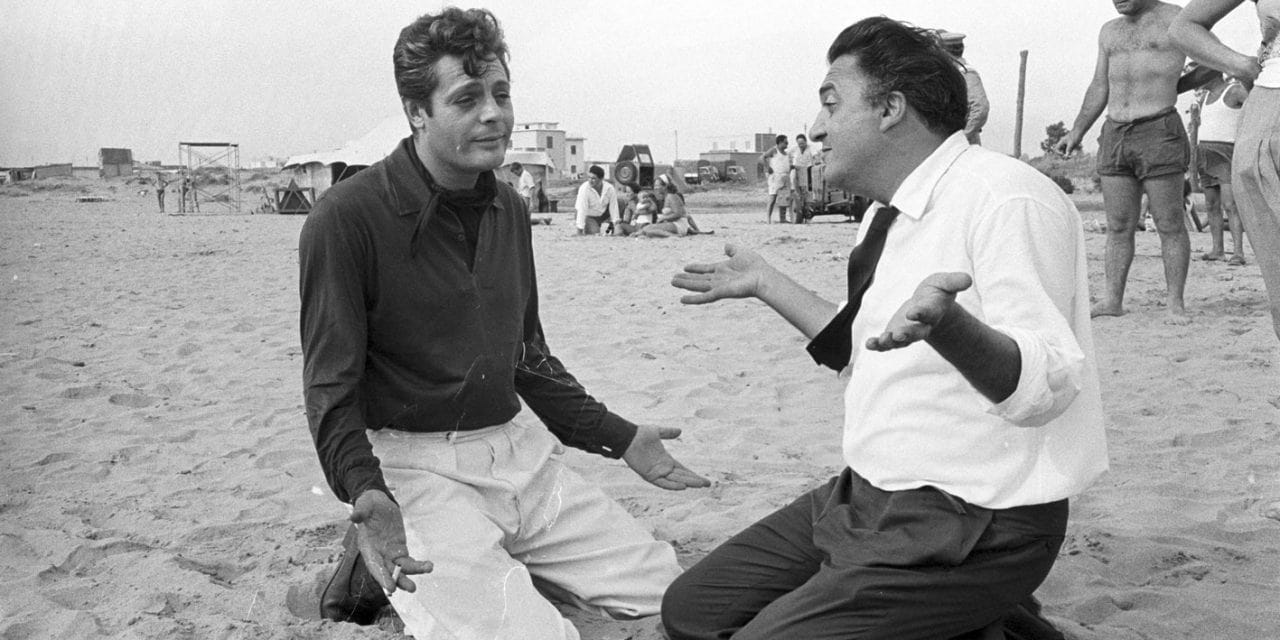

But the origin of that idea — this illusion, this seductive image — came from Federico Fellini. For a long time, he worked as a screenwriter, shaping the scenes of Italian Neorealism in the 1940s and early 1950s. Yet when he was finally given the chance to experiment with his own world — to drift away from realism and gradually bend it into illusion and surrealism — the transformation began. It started with La Strada in 1954, and six years later reached its most iconic form in La Dolce Vita.

This film, perhaps more than any other, shows cinema as a spiritual projection of the auteur himself. First, Fellini infused it with his own personal background — his relationship with Rome, the socialites, celebrity culture, journalism, and Catholicism — all turned into cinematic components. Second, Marcello Mastroianni served as Fellini’s pure alter-ego: a journalist seduced by the beauty of Rome yet trapped in its decadence and shallowness, wrestling with inner virtue he hoped to realize. And third, Fellini injected surrealism, reflecting his belief in Jungian psychoanalysis and the dream as a revelation of human inner truth.

Consider all of this, and you’ll see that La Dolce Vita (and many other Fellini films) are byproducts of his inner world, his vision, his ideology — transformed into cinema.

Jean-Pierre Melville — The Resistant Samurai

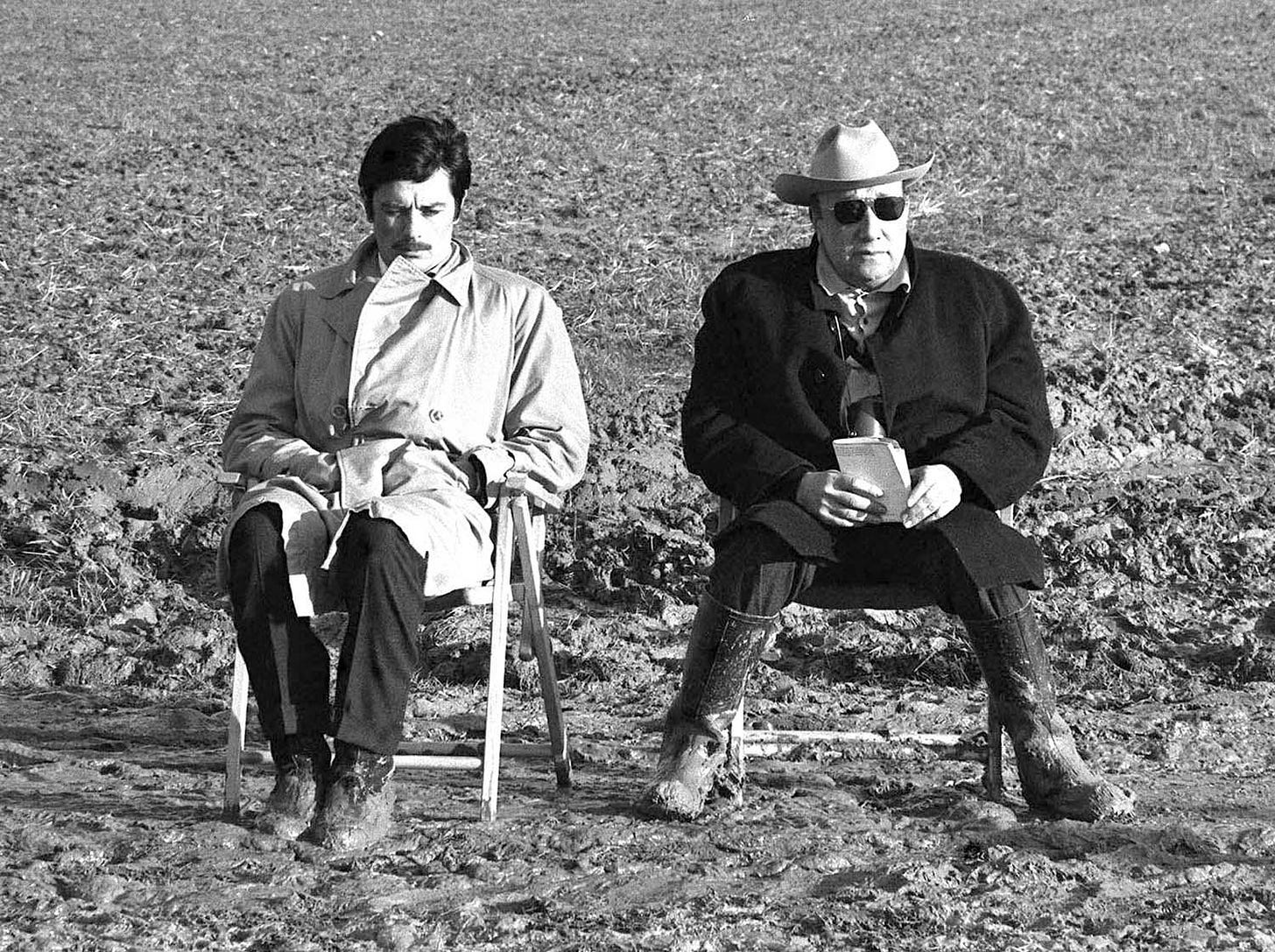

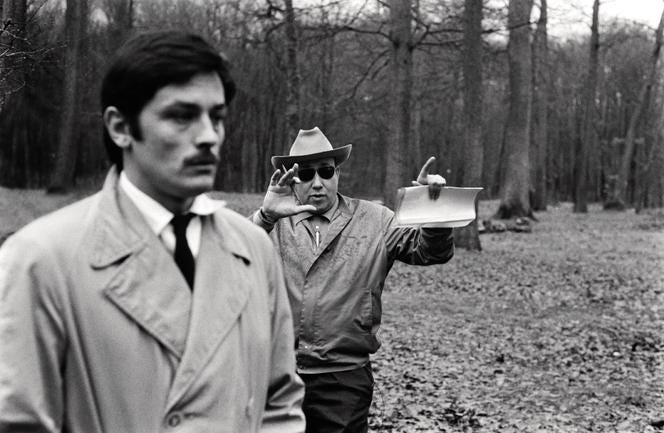

If there is one man responsible for the idea of the stoic character navigating a chaotic world — often as an underground criminal or notorious killer — it is Melville. His most iconic work could only be Le Samouraï, a film that channels his worldview: a life guided by honor, discipline above all else, and an existence devoted not to pleasure but to duty — even at the cost of death.

Many of his films were born from his own experience fighting in the French Resistance, which forged his personal code of honor, loyalty, and existential philosophy in the face of uncontrollable forces.

Across his iconic works — with actors like Belmondo, Delon, and Ventura embodying his characters — all were shaped by Melville’s worldview and vision of cinema. Through his lens, gangster films became something more: an exploration of existential codes and stoic solitude, later influencing filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino, John Woo, and many others across generations.

These two auteurs are among the few who demonstrated that cinema is more than an entertaining medium to watch and forget. It was meant to be deep, reflective, individual, and even spiritual. This kind of cinema was widely celebrated in the 1960s — through Antonioni, Godard, Truffaut, Resnais, Tarkovski, Bergman, Kurosawa, and many more.

That was the Golden Period of Cinema at its finest. And while the modern masses may have forgotten its existence, you — here and now — can use what is called cinema to either change the trajectory of your life or simply understand yourself more deeply.

How This Medium Can Change Your Life (Like It Did to Mine)

When you look into the core idea of cinema, it is a form of self-projection — a world that manifests the beliefs, ideologies, and life of a creator into a narrative on the screen.

And whether you’re aware of it or not, humans are creatures who understand the world through stories. We make sense of life by associating who, what, where, how, when, and why.

Now, not every movie is created to move or shift something inside you — but trust me, there is always the right one that does, for everyone.

In my case, my life was shaped by two things cinema offered me: ideal aspiration and elegance among absurdity.

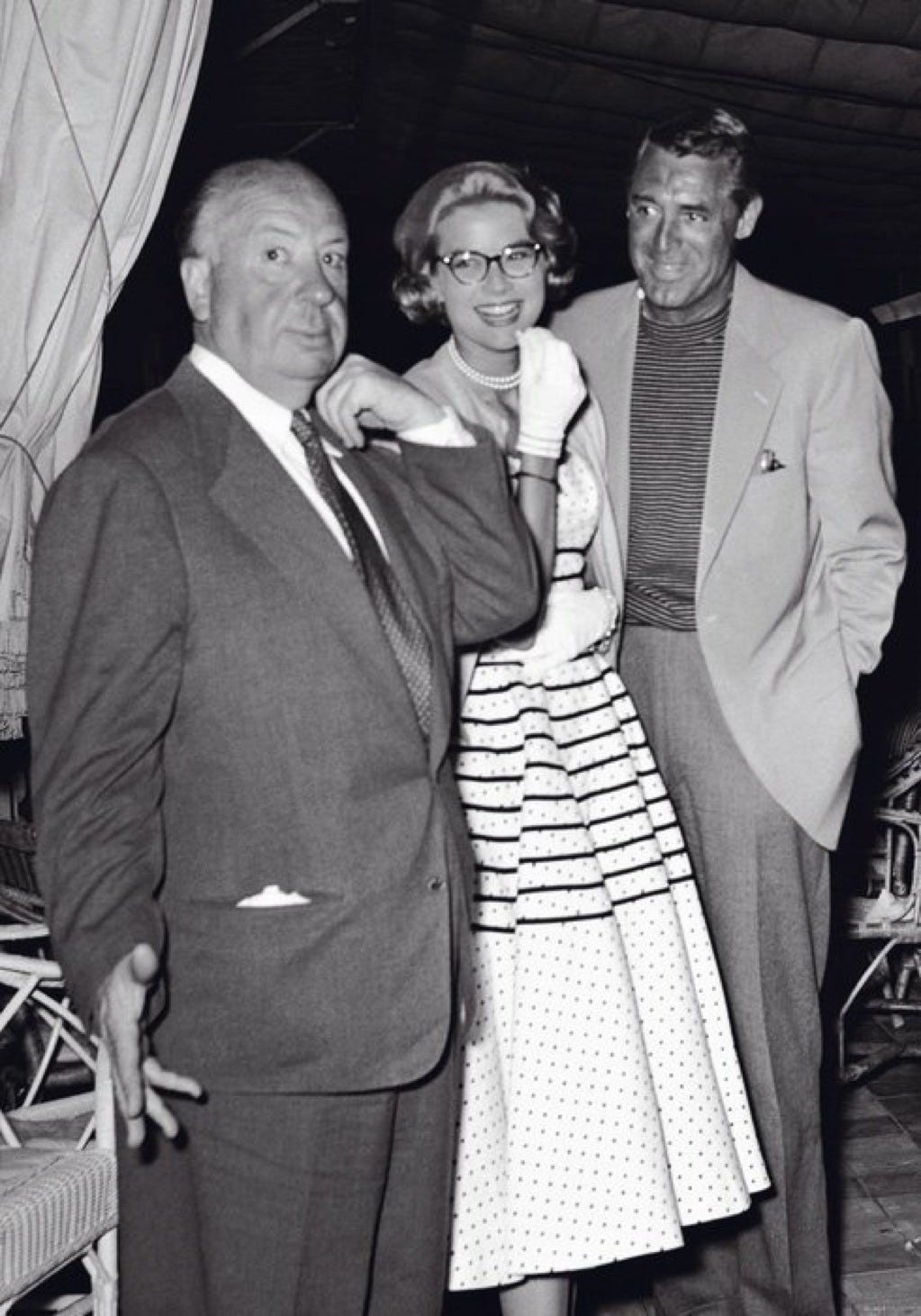

Ideal aspiration came when I discovered the myth of the gentleman that Hitchcock laid out in his fantasies To Catch a Thief and North by Northwest. Cary Grant starred in both, and through Hitchcock’s direction his portrayal became nothing less than a blueprint for me to develop myself toward that fantasy — even if it might take decades, or the rest of my life, to reach it.

Elegance among absurdity is what I observed through continental cinema of the 1960s — in La Dolce Vita, Le Samouraï, L’Eclisse and many more — films that portrayed men and women navigating an age of post-war uncertainty, yet still carrying themselves with “elegance” in style, way of life, and cultural landscape.

When you begin to see cinema through the lens of psychological association — as a bridge between your inner self and the world of the auteur — you start to treat it as an art form that nourishes and cleanses your spirit. A gateway to discovering another part of yourself and absorbing it, to make yourself a higher version of being.