This One Mental Shift Will Make You More Intelligent Than Most People

How to See Through Modern Narratives and Think Beyond Good vs. Evil

After almost a year since my initiation to explore the idea of living as an elegant individual—or to be precise, a gentleman…

There’s a common objection hidden beneath the crucifixion of this idea:

“What do you expect to gain or be from a bygone era—especially the 20th century?”

“What’s so good about romanticizing patriarchy, global warfare, and a restricted way of life?”

When I first encountered these objections, all I could think was:

“Is that really what I’m sharing?”

It’s obvious that the idea of a gentleman is heavily associated with early to mid-20th-century society.

In the end, it’s the byproduct of idealizing the noble version of a man—once limited to birthright during the 16th–17th centuries—that evolved into a chosen way of being that every man aspired to.

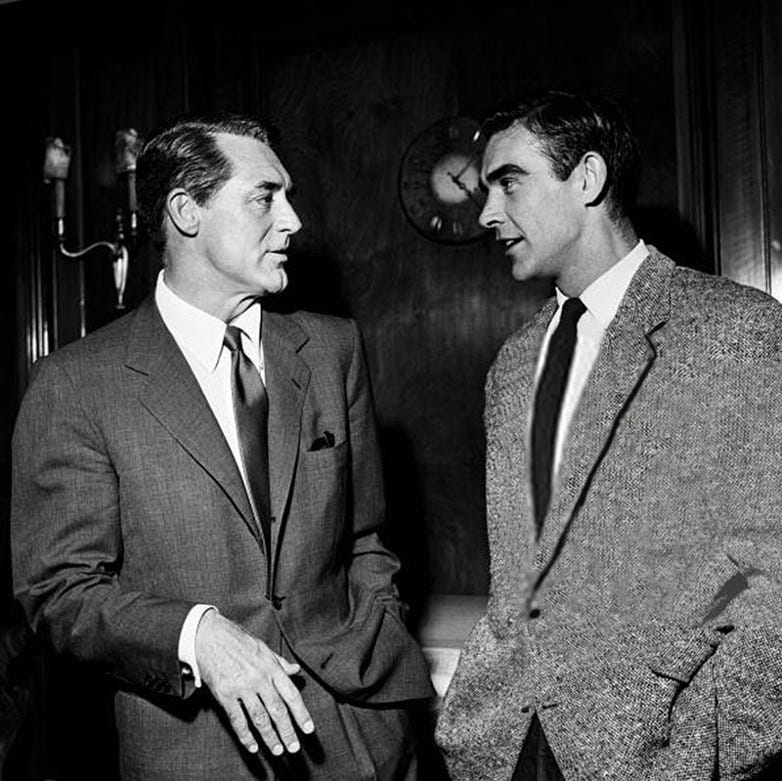

That’s why I—and many modern men—admire iconic names like Cary Grant or Sean Connery.

Not just for their external excellence through the clothes they wore and how they wore them, not just for the charm and suave, debonair demeanor they embodied—but because it’s a treasure of a bygone era that can’t be found anymore in the 2020s.

Howeverm, whether because of mass media, shifting social agendas, or the rise of a casual-first mindset, the ideology of the gentleman—once glorified through Grant and Connery—has lost its place.

Often perceived as obsolete by the masses.

And that perception has led to objections like:

“What do you expect to gain from the 20th century?”

Since the way a man (or a woman) carries themselves, the care they give to their appearance daily, and the way they put others at ease—these are no longer the ‘standard’ in the 21st century…these qualities have been hidden in plain sight for many.

And whenever the image of a man with a side-part hairstyle and a tailored suit, or a woman in well-groomed hair and attire resembling the Dior New Look silhouette of the 1950s appears….

It often gets talked down with disgrace and undesirable historical context:

Inequality, gender discrimination, the harshness of war times.

And I totally agree—those incidents are far from aspirational, and I too don’t believe they should come back…

But, ladies and gentlemen, here’s my question:

“Can we, as humans, explore history, observe the past, and select only the virtues from bygone eras—without dragging back the chaos that should stay as relics?”

To understand this, I’ve tried my best to see things through the lens of those who critique the romanticization of elegance from the past.

That led me to this concept, which I call - Chronological Reductionism.

“Chronological Reductionism is the intellectual fallacy of judging the past entirely by the moral standards, ideologies, or sensibilities of the present—and then reducing everything from that past to either ‘good’ or ‘evil’ based on that lens.”

From this definition, several components can be dissected.

The first of interest is this binary idea of judging something as either ‘good’ or ‘evil’.

This is the classic philosophical debate that every great thinker has tried to tackle.

And, as you might guess, there are countless frameworks—but the great names you probably know all lean toward a common ideology:

From Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics:

“Virtue, then, is a state of character concerned with choice, lying in a mean… this being determined by reason and as the man of practical wisdom would determine it.”

To Nietzsche’s provocative assertion in Beyond Good and Evil:

“There are no moral phenomena at all, only a moral interpretation of phenomena.”

Even Shakespeare captured this essence in Hamlet:

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” — Hamlet, Act II, Scene II

All of these crystallized ideas lead to this:

To judge anything entirely as purely good or purely evil is inapplicable to human experience.

To assume that:

If something comes from a morally flawed era, then all products of that era are invalid.

There is no such thing as timeless virtue, only contextual ideology.

You cannot extract the useful or the beautiful without endorsing the ugly.

These assumptions simply do not make sense by their own nature.

And let’s simplify this—cutting through all the abstraction of philosophy:

Can’t a mere human have the ability to dissect components of the past, and choose only what is desirable and morally right based on universal virtues?

To claim that: If you aspire to the Elegance of Cary Grant (or 20th-century gentlemen), then you must also be endorsing misogyny or global war tensions

Is like saying: If you read Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, then you agree with slavery.

(Which, obviously, is not the case—I assume.)

That’s why one thing modernity can benefit from is letting go of Chronological Reductionism and starting to see the world as it is—containing both good and evil, as nature always has.

‘Constructive Deconstruction’ — The Key to Modern Intelligence

There is a philosophy from the French neo-classical thinker Jacques Derrida—Deconstructionism.

To understand his concept, consider his quote:

“That is what deconstruction is made of: not the mixture but the tension between memory, fidelity, the preservation of something that has been given to us, and, at the same time, heterogeneity, something absolutely new, and a break.”

Derrida’s purpose was to break down the control that systems have over humans.

To expose contradictions and instabilities within ideologies—showing that no part can ultimately serve as an objective foundation.

However, my take on “Deconstruction” aims not for disruption, but for liberation and evolution.

So, ladies and gentlemen, allow me to introduce Constructive Deconstruction - The Antidote to Chronological Reductionism.

If the objection to reclaiming elegance in modernity is:

“Those so-called virtues came from a bad time, so they’re bad.”

Then Constructive Deconstruction allows us to extract their essence from the flaws they were wrapped in.

And to implement this, you need just 4 questions:

What is the core structure beneath this?

What is essential vs. what is contextual?

What is virtue, and what is just veneer?

What can I salvage, reformat, and rebuild?

Let’s take a classic example:

The suave, debonair secret agent who has survived six decades of pop culture—James Bond, especially from Sean Connery to Pierce Brosnan.

“I think you’re a sexist, misogynist dinosaur. A relic of the Cold War, whose boyish charms, though wasted on me, obviously appealed to that young woman I sent out to evaluate you.” — GoldenEye, M to Bond

Let’s deconstruct this:

Q: What is the core structure beneath the idea of the gentleman in Bond?

A: A purpose-driven man, charismatic in socialization, confident in elegance, and composed under pressure.

Q: What is essential vs. what is contextual?

A: What resonates today is the development of character. Bond is a man who knows what he wants, understands his purpose, and navigates life with sophistication. The context—mid-20th-century ideals, societal rigidity, inequality—is not the core.

Q: What is virtue, and what is just veneer?

A: Timeless virtues include his attire, composure, grace under pressure, and purpose-driven action. The sexism, outdated behavior, or cold war attitude? Just veneer—not worth carrying forward.

Q: What can I salvage, reformat, and rebuild?

A: The essence of class, charm, and decisive character—reintegrated into modern life where social context has evolved. The poise without arrogance, the strength without rudeness—that’s the masculine ideal we can still apply (and arguably, need) today.

That’s how Constructive Deconstruction works.

It’s how you can:

Study Marcus Aurelius without reviving the Roman Empire.

Admire samurai discipline without reviving feudal Japan.

Honor 20th-century gentlemen and ladies without reviving their era’s gender roles.

While I understand most people may struggle with this, due to the mental demands of understanding deep context, letting go of ideological purity, and navigating complexity without needing simple labels to hide behind…

But for those who can see through the modern condition—and deconstruct the past with constructive purpose—then you can redirect the energy of old systems and the virtues of a bygone era into something new, potent, and alive—and relevant in the present.