Why Mid-Century Was Humanity’s Last Great Frontier

Even amid Cold War tension, discrimination, and fragility

I was once told—and asked—by both random encounters on the internet and real-life figures whom I respect, something along the lines of:

“Patrick, why are you so attached to and romanticize the early–mid 20th century?”

“You know that those periods were full of chaos and not-so-romantic things, right? Global warfare, discrimination, inequality between sexes, financial breakdowns…”

“What’s so special about it?”

Well, ladies and gentlemen, the 20th century is an era that has been interpreted in many different ways.

If you are in your 20s or 30s, you probably only experienced the 90s. If you’re in your 40s or 50s, then you might have tasted the flash of free spirit and disco during the 70s and the utilitarian cosmopolitan world shaped by synth-pop of the 80s.

And if you’re in your 60s or 70s (which amazes me if you stumble upon this essay), then you, sir and madame, experienced the world during the mid-century firsthand. Though it probably wasn’t that glamorous, since that period was your childhood—and by human nature, you were likely not so inclined to embrace the traditions of your parents’ era. (Yet, this varies by individual experience.)

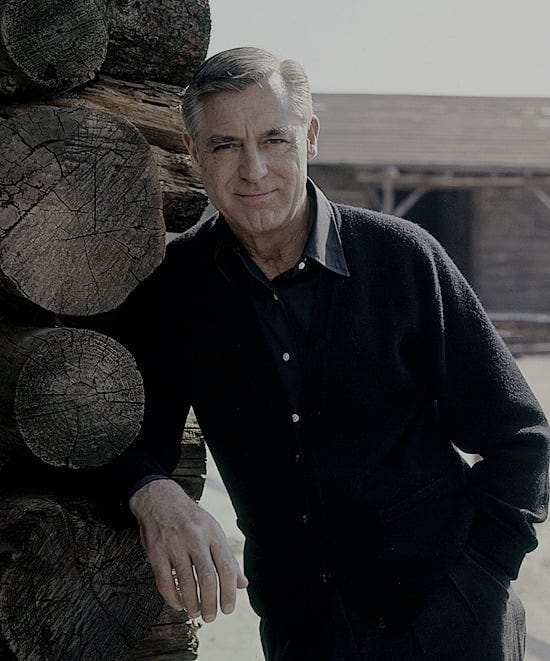

The thing is, people who can actually say what it felt like to live and experience the 1950s as an adult are almost all gone. (With the passing of Robert Redford on September 16th, it symbolically marked the end of an era.)

To make an absolute statement that the mid-20th century was a universally “great era” might be beyond the scope of what I can write. But if it’s the idea of the legacies of elegance it has left for humanity—this is where I can fully orchestrate and narrate.

That mid-century was arguably the last period where humanity experienced, embodied, and expected elegance on a daily basis.

It was an era where culture was lived, celebrated, and refined in ways that people in the 2020s now widely reminisce and appreciate. You can see it in the countless comments on Dean Martin or Frank Sinatra performances, or Audrey Hepburn and Grace Kelly films—things like:

“They don’t make things like this anymore.”

“I wish the world was like this.”

However, there’s another school of thought—one that says:

“Nostalgia is for escapists, for those who cannot embrace the present moment.”

The truth is, both sides reflect the nature of being human—and those who can see beyond this will begin to view life from a different paradigm.

Human Nature and the Nostalgia Phenomenon

“Teddy told me that in Greek, nostalgia literally means the pain from an old wound. It’s a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone.” — Don Draper

The root cause of why realizing the sweet old days is so alluring, seductive, yet aching, is that it’s a deeply rooted feature of consciousness itself—tied to memory, time, and identity.

Humans, arguably, are the only animals truly aware of the passage of time and the inevitability of death. We subconsciously know that every moment that passes is irretrievable, and nostalgia is the psyche’s way of tasting immortality—by reviving what’s gone, even if only as an image. It’s seductive because it grants you a fleeting illusion that the past is not lost. It’s haunting because the very act of remembering reminds you that it is lost.

That said, every nostalgic rush is also a wound reopening.

It confronts you with the irreversibility of time.

You can never walk back into your childhood home as the child who once lived there.

You can never hold a dead friend again as you once did.

You can only ache at the ghost.

This is why nostalgia always carries pain: because it is not about the memory itself, but about the absence of the living moment it once was.

And as you can guess—this thing called nostalgia is not a mere incident that happens to a specific few, but a universal truth of human nature.

(In my last essay, I fully elaborated how narrative—or story—and human identity are biologically wired together.)

In essence, to be human is to live in narrative, to thread the past into the self of the present. Without nostalgia, you’d be just a soulless machine—functional, but hollow. That said, the universality of nostalgia reveals a deeper truth: humans are not beings that have memories; humans are memories. That’s what makes us a unique kind of creature—one that stands above all in the biological system.

Now, one question remains: How can nostalgia work on a memory or experience that one never lived before? In our matter of interest, this is the prime period of the mid-20th century.

One thing about memory is that it can be constructed not only through direct, physical, real-life experience, but also through the culture and collective imagery you’re exposed to. In the end, the core ideology of nostalgia is about narrative—the story that creates an emotional bond, one that later turns into an endless wound since it cannot be retrieved.

So it’s fair to say that nostalgia isn’t about the past—it’s about the gap between what is and what could be.

When you hear Frank Sinatra or see Audrey Hepburn’s silhouette on screen, you’re not just observing history—you’re plugging into an aesthetic memory preserved by generations. Though it’s not your memory biologically, it becomes yours symbolically.

Here’s the interesting part: most comments that say “They don’t make this anymore” on YouTube clips of 1960s Rat Pack crooners or Breakfast at Tiffany’s are not yearning for the 1960s per se, but for the archetype of elegance, ritual, and authenticity—a template of refinement and enchantment that the present lacks.

That said, chronologically, people can’t actually want the era—they never lived it (and of course, that period was riddled with problems like wars, discrimination, repression, etc.). But what they’re truly yearning for is a lost mode of existence: slowness, polish, sensuality, presence.

That’s why nostalgia occurs. It’s the soul recognizing something it needs but cannot find around it—since the modern day, full of speed, casualness, and noise, no longer gives grace to masculinity, mystique to femininity, melody to music, or ceremony to living.

Now, the classic argument from another school of thought—those who see yearning for the glamour of the past, nostalgia for the old days, as mere ‘coping for the lack of ability to stay in the present’—often goes like this:

“What’s so good about an era of racism, sexism, and global warfare that caused paranoia and uncertainty?”

At surface level, this might sound rational. But those who argue this way are missing a single intellectual ability that makes humans virtuous beings:

The ability to deconstruct the components of the past and turn them into construction.

(If you want a full ideological explanation, I’ve written an entire essay on this before.)

But let me ask you: if going back for virtue in the past means we must gather everything from those eras, then does that mean…

People who read Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations must be advocates for slavery?

People who quote Martin Luther King Jr. must also embrace his documented sexism and personal failings?

People who love Renaissance art must also long for the plagues, corruption, and brutal inquisitions of that time?

This is, of course, absurd.

The solution—the truly noble, virtuous one—is to deconstruct, discern, and reconstruct. To identify the ideas that stand as timeless and great, which may have been lost in this era, and resurrect them in a way that does good in the present moment.

Take the Renaissance, for example.

Thinkers and artists like Da Vinci and Michelangelo rooted their wisdom in ancient Greece and Rome—societies built on slavery, inequality, and blood sport—yet from that admiration, they created philosophy, art, and science that still define civilization.

This period itself proves that greatness comes not from rejecting the past, but from deconstructing it, extracting the timeless, and reconstructing it into something greater.

(Imagine if they had followed the logic of “all or nothing.” The Renaissance would never have existed.)

So—ladies and gentlemen—it is now time to revive the virtues of the mid-century: the last frontier of glamour, elegance, and depth in human existence.

Five Legacies from Mid-Century - The Middle Ground Between Old-World and Modernity

If you look back at the timeline of the 20th century, it can be dissected into three distinct periods:

Early (1900s–early 1940s): from the Edwardian era to WWII.

Middle (late 1940s–early 1960s): the Post-War Era.

Final triad (late 1960s–1990s): the postmodern stretch, from counter-culture to the decade before the new millennium.

The beauty here is that you can see a pattern—a big picture of what each era represents. The early 20th century still clung to restrictive traditions, the remnants of the 19th century: a world still tethered to the “old world.”

Meanwhile, by the late 20th century, society had undergone massive shifts. Rules were bent and broken; revolutions reshaped culture everywhere, shifting the paradigm into something far more casual.

However, there exists a middle ground between old-world glamour and postmodern dynamism: the mid-20th century.

This context was shaped heavily by the aftermath of WWII. The world had turned from chaos toward optimism—swinging from devastation into a hopeful belief that “finally, we’re about to enjoy life and experience fine things once again.”

Of course, much of that optimism was likely a coping mechanism. After all, the Cold War loomed, bringing decades of subtle tension through nuclear threats, proxy wars, and unpredictable economic and political shifts. Yet, despite all of this, the era still held the line as the last frontier of elegance.

You can observe this through five cultural elements that left legacies lasting to this very moment.

1. Sartorial Optimal (Beyond the Golden Age)

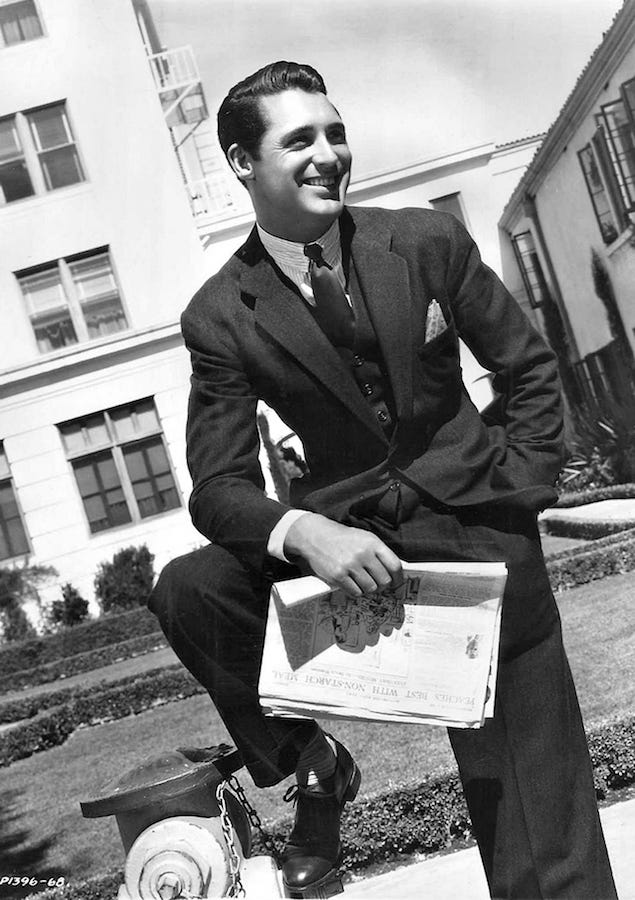

In the realm of menswear, whenever one thinks of its “Golden Age,” the 1930s always come to mind. It was the peak of tailoring—variety in fabrics, patterns, and cutting styles—all of which can be observed in vintage Esquire illustrations of the era, and of course, in the hundreds of Hollywood films during its own Golden Age.

The thing is—even for me as a true connoisseur of sartorial style—truly emulating the garments and silhouettes of the 1930s in the 2020s feels clearly out of place. And by that, I don’t mean they are not timeless or that they are too fashion-driven. Rather, they are simply out of sync with today’s modern landscape, which favors casualness and comfort.

To wear neckwear apart from the standard tie (like a cravat), to accessorize with collar bars, or to don waistcoats and full three-piece suits—the modern context is unforgiving to such displays. And if you subscribe to the school of thought that context is crucial to determining elegance, then you will know this truth: the more you dress out of scope with context, the less elegant, effortless, and subtly alluring you appear.

And here is where mid-century sartorial flair enters the picture.

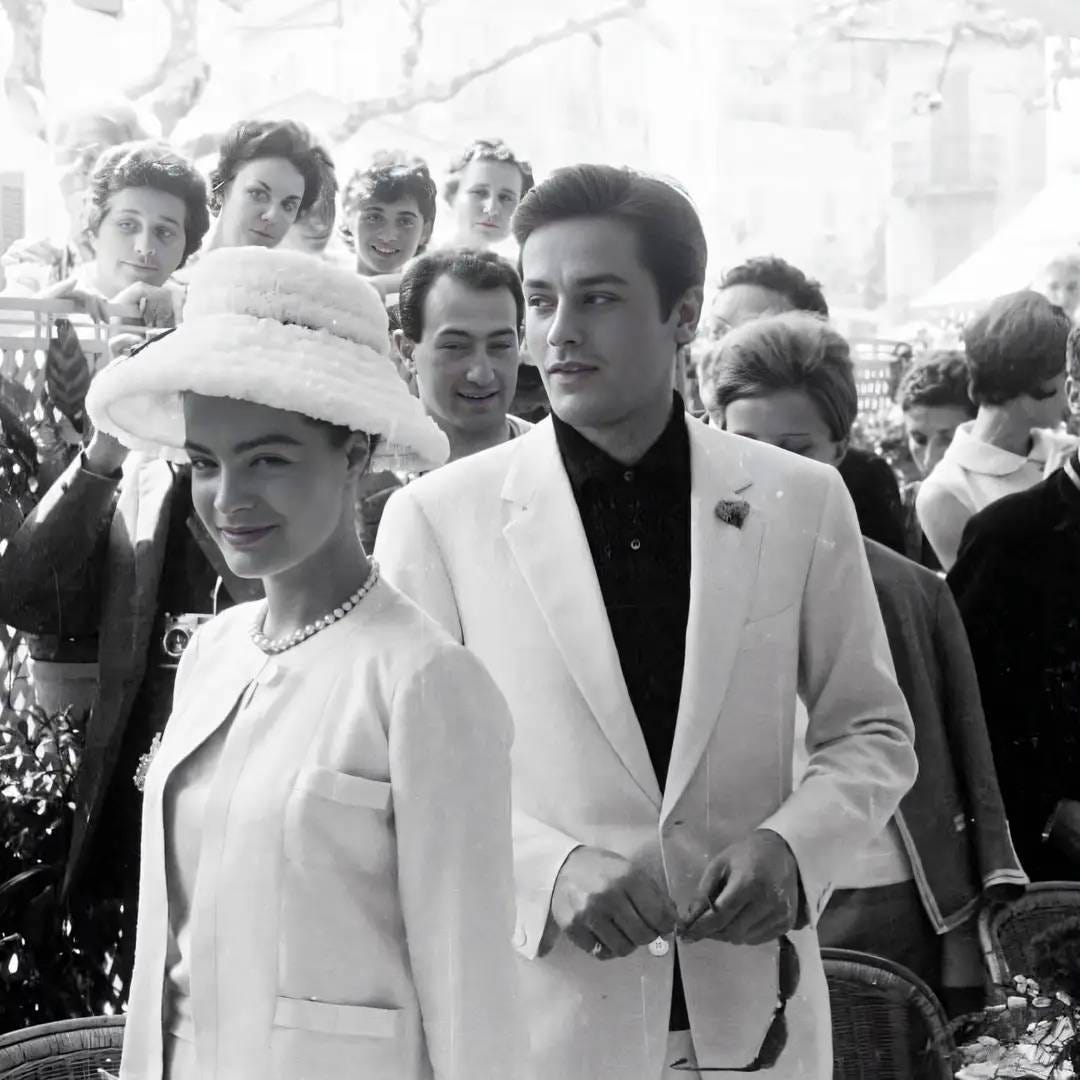

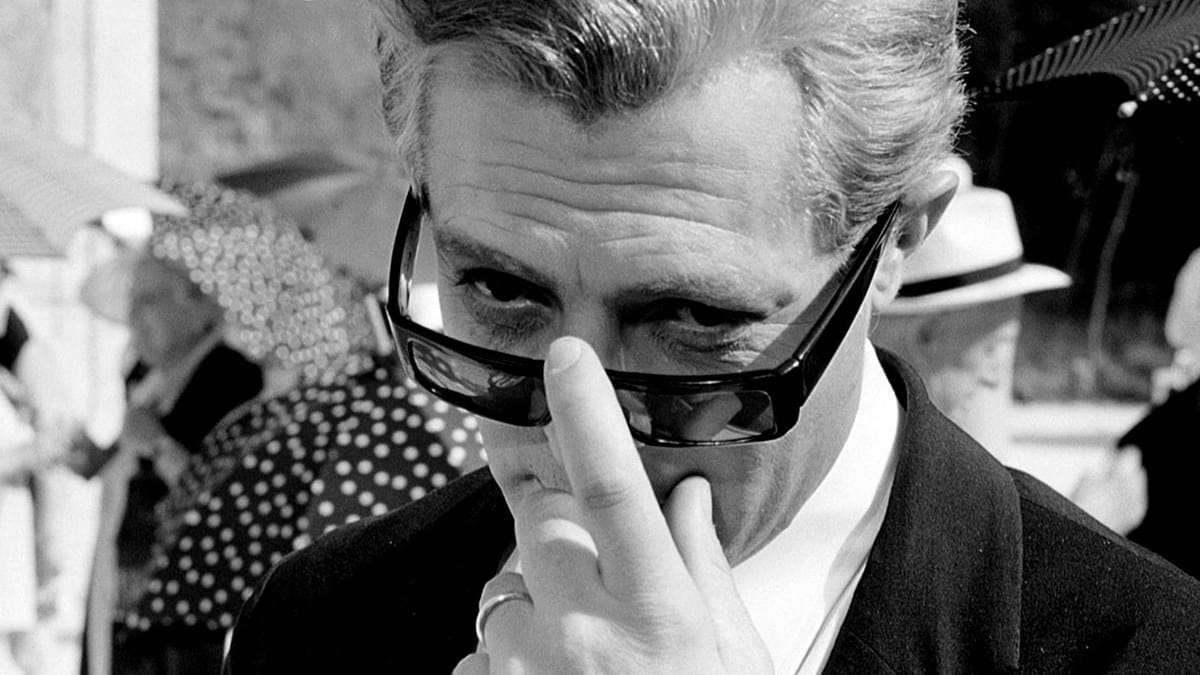

The evidence can be seen in two images of Cary Grant…one from the 1930s

And this one from the 1960s.

Now tell me: which one would appear more elegant in the 2020s if worn today?

The answer is clear: the 1960s.

Why? Because the mid-century streamlined the excesses of menswear.

Silhouettes tapered into something leaner, yet still full and masculine. Casual elements were normalized—polo shirts and OCBDs instead of dress shirts all the time, loafers instead of laced shoes. (In fact, by the 1960s Cary Grant himself was almost always seen wearing loafers instead of his Oxfords.)

My statement here is this: everything in the sartorial realm during the mid-century can still be worn elegantly in the 2020s without ever feeling “out of place.” Ivy Style reigned supreme in the 1950s. Evening wear evolved as black tie became the standard (while white tie became almost obsolete for most social events). And all this while traditions of bespoke tailoring, timeless design, quality cloth, and craftsmanship still held strong—before the ready-to-wear industrial boom of the 1970s that carries on to this day.

2. Romance of Couture (Golden Age of Haute Couture)

Speaking of bespoke, let’s look at the other side of menswear: womenswear—and the equally famous term, Haute Couture.

As you might guess, its origin is French. Haute = High, Couture = Sewing. Thus, Haute Couture means “High Sewing,” or in simpler terms: high-class garment.

To be considered Haute Couture, a garment traditionally must:

be an entirely new design, made-to-measure for private clients

be crafted with extreme technical mastery by hand

be produced in Paris ateliers with a minimum number of skilled artisans

be shown twice a year by accredited houses under the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture

The seeds of glory were planted and pioneered by renowned icons such as Jeanne Lanvin and Coco Chanel in the early 20th century.

Lanvin is often considered the “mother of Haute Couture.” Not the very first couturier, but the premiere figure who brought an almost ethereal femininity into fashion—through ornamented embroidery, pastel tones, and romantic silhouettes. Her work blurred fashion with artistry.

As for Chanel, little description is needed. Her projection of ideal femininity broke the norm—a woman with flair and unique spirit—expressed through jersey fabric for women, sportswear-inspired ease, and the iconic little black dress of the 1920s. She stripped couture of ornamental excess and transformed it into a language of modernism and freedom.

Even though WWII almost destroyed Haute Couture (and Paris as a whole), a resurrection came with names you will recognize: Cristóbal Balenciaga, Christian Dior, Hubert de Givenchy, and the young Yves Saint Laurent in the late 1940s–50s.

It began with Balenciaga (certainly not the “Balenciaga” you see today with avant-garde sneakers and streetwear, but the Balenciaga of precise architectural elegance). He created a new standard and norm for Haute Couture, and from his presence, a new fire was lit.

Dior reclaimed the glamour of femininity with his New Look collection of 1947, reshaping the entire silhouette of women in the 1950s. Givenchy brought aristocratic flair into his design philosophy, dressing Audrey Hepburn and showing the world the art of simplicity. And then there was Saint Laurent, the young genius who became Dior’s creative director after Dior’s passing in the late 50s, establishing himself with a fresh, daring lens on feminine myth.

By the last period of the mid-century, these men had pushed Haute Couture to its apex—making it not merely clothing, but a theater of identity, aspiration, and craftsmanship at its absolute peak. This was before the rise of ready-to-wear and youth culture fractured its dominance.

Every modern designer, without exception, looks back to this period. They study it, take inspiration from it, and build their collections upon its legacy—even today.

3. Mid-Century Interior Design

I first noticed this element from the TV series Mad Men. Every time I saw Don Draper’s apartment, it provoked something in me: the idea of clarity, functionality, and warmth without excess.

What intrigued me even more is how more and more people today seek inspiration from—or even design their homes entirely around—mid-century interiors. And there’s a reason for that.

Emerging in the post-WWII era (late 1940s–60s), this style reflected both optimism and pragmatism. Homes needed to be efficient yet elegant, democratic yet stylish. The movement emphasized clean lines, open plans, and organic forms, often drawing from Bauhaus rationalism and Scandinavian humanism.

This spirit can be seen in the era’s iconic designs:

Eames Lounge Chair & Ottoman (Charles & Ray Eames, 1956)

Perhaps the single most recognizable emblem of mid-century design. It merged luxury with modernity: molded plywood and supple leather crafted for comfort, but stripped of old-world heaviness. It embodied the era’s dream of modern living—functional, stylish, democratic, yet indulgent.

Noguchi Coffee Table (Isamu Noguchi, 1947)

A sculpture disguised as furniture. Its biomorphic glass top rests on two interlocking wooden supports, blending art, form, and function into one. It symbolized the organic, humanist side of mid-century design, where even everyday objects carried the grace of modern sculpture.

Tulip Chair (Eero Saarinen, 1955–56)

Saarinen’s revolt against “the slum of legs.” With its single pedestal base and fluid fiberglass form, the Tulip Chair represented the futuristic purity of the period—simplicity, space-saving practicality, and an elegance that still feels ahead of its time.

Together, they capture the mid-century trinity: comfort made modern (Eames), art made functional (Noguchi), and form made futuristic (Saarinen).

4. Depth of Artistry

What you can notice about artistry and culture during this period is the depth and substance of things. Much of the art of the mid-century went far beyond superficial beauty or easy accessibility. It required depth, dedication, and mastery—the very reason cinema, music, and culture from this period remain iconic, alluring, and celebrated to this day.

Take cinema, for example. Before this, Golden Age Hollywood was the global powerhouse, controlling both the narrative and the way films were made. But with Italian Neorealism in the late 1940s, led by Rossellini, and most importantly the French New Wave of the late 50s and early 60s, the very concept of “film” was redefined into “cinema.” (I once elaborated on this idea in another essay.) These movements broke conventions, yet still preserved elegance and sophistication, keeping cinema aspirational. For cinema, the mid-century was the pinnacle where style met substance.

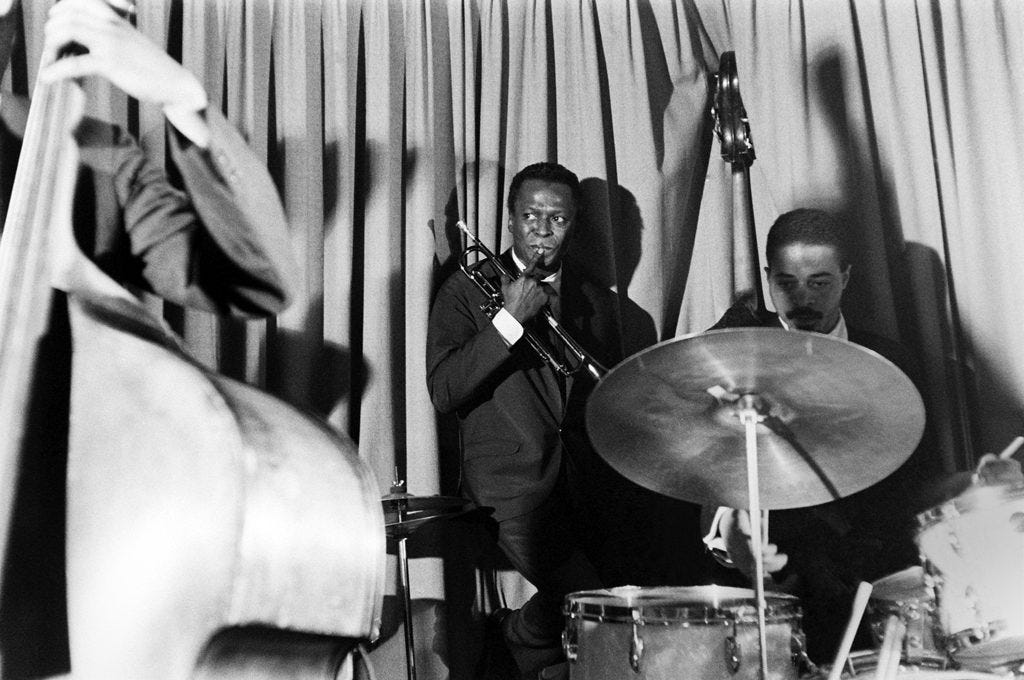

On the music side, while new genres like Rock ‘n’ Roll—led by Elvis, Dylan, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones—rose to prominence, jazz remained the defining front of popular music. For mature audiences, crooners and big bands—the old-world legacies of Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Count Basie—were the soundtrack of choice. For younger, sophisticated listeners, the modern edge of bebop jazz, led by Miles Davis and Dave Brubeck, offered a deeper path of appreciation. And as you might guess, jazz could never be played shallowly—it demanded true mastery.

Thus, artistry in the mid-century stood as the last frontier of elegance and depth—before disco and synthetic music of the 70s and 80s arrived (let alone the beat-trap of the 21st century).

5. Optimism in Life Amid Uncertainty

Still, if there is one virtue the mid-century has left humanity—one that stands as its most humanist—it is this: that optimism in life can be lived even amid uncertainty.

I do not believe that the people of that era, even those who hailed the “American Dream,” were ignorant of how fragile the world was. They knew the destructive power of the atomic bomb. They lived with daily tension between left and right, East and West. And yet, they found a way to live.

The thinkers of the period gave frameworks for navigating existence in a fragile world:

Albert Camus declared that even though life has no inherent meaning, we must embrace the absurd with defiance and dignity. His optimism was not naïve—it was rebellion against nihilism.

Viktor Frankl, Holocaust survivor and author of Man’s Search for Meaning (1946), argued that even in the most dehumanizing circumstances, life’s worth lay in finding meaning—through love, work, or suffering itself.

Jean-Paul Sartre claimed that humans are “condemned to be free,” with no God or essence to guide us—only the burden of choice in a meaningless universe.

Together, they gave humanity a map to navigate meaning in times of uncertainty.

And this, I believe, is the anchor we can hold onto in the 2020s and beyond. Our own time is chaotic and uncertain. One technology can disrupt a way of life. One invention can erase entire careers. One movement can trigger a chain reaction that shakes economies and nations.

Looking back at the mid-century is not just about celebrating elegance and glamour. It is about seeing how life itself can be lived—deeply, beautifully—even amid fragility.

I hope you found what you were looking for in this essay, and I look forward to seeing you in the next one.

Until then, take care and have a great day.

Au revoir,

Patrick